Karolien Vanbroekhoven (Research Manager Sustainable Chemistry at VITO) already indicated as much in her presentation on the Biorizon Shared Research Centre at the beginning of the conference. Without cooperation between the Flemish Institute for Technological Research (VITO), the Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research (TNO), the Energy Research Centre of the Netherlands (ECN) and the Green Chemistry Campus, this border-transcending research centre never would have got off the ground. By bringing together expertise in divergent areas, it was possible to quickly act in all areas, technological, as well as economic. This significantly accelerated knowledge development and various ongoing research projects within Biorizon, one by one, entered the upscaling phase.

Stimulating cooperation among educational institutions individually, as well as with companies, and the efficient use of (regional) research centres consequently was one of the most important basic principles underlying the BBE project. The project had its start in 2016, with the objective of developing teaching materials for educating the specialists needed by the biobased economy now and in the future. This at all levels, ranging from senior secondary vocational education (MBO) to the university level. While avoiding the possibility of too much overlap in activities, facilities and teaching methods.

Building-biology and blood-lamp

A number of interesting speakers during the concluding conference addressed a number of divergent topics relating to the biobased economy. Mark Boschman of Roosros Architects, for example, demonstrated the importance of circular and biobased design for a contemporary architectural firm. In its designs, Roosros links energy efficiency to health and incorporates buildings constructed from recycled materials. According to Boschman, this means that we need architects who think differently, who learn to look at nature, who know what the materials they work with are made of and what the impact of using these materials is, for example on biodiversity: ‘we must become building biologists.’ Biology does not form part of most building-related education programmes.

Achille Laurent, researcher in the Sustainability of Biobased Materials Team at Maastricht University, presented a lecture on Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) for establishing the sustainability of biobased products in comparison to traditional products. Ravi Bellardi, Brand Management Specialist at the GLIMPS design firm outlined workshops and training programmes for designers interested in incorporating biobased materials into everyday utilitarian objects. What comes to mind here is biomimicry, creations made using mycelium and microbial leather, as well as original, less practical objects such as the blood-lamp; that gives off light when you break it and cut yourself on the glass fragments.

Panel Discussion

During a lively discussion, day chairman Florian Dirkse put various conjectures to a panel with diverse backgrounds: Nico Osse, Managing Director of the bioplastics manufacturer HemCell, Rop Zoetemeyer, Managing Director of the Biobased Delta Foundation, Bart Wuyts, CEO of the knowledge and innovation centre Blenders, Geert Mol, Project Manager Biobased at HZ/Centre of Expertise Biobased Economy and Hans Goossensen, Director Municipality of Dordrecht.

The first two conjectures were about having the business community bring education in-house, or the reverse, and the transition needed in the education sector to be able to train biobased specialists. Bart Wuyts observed that we do not only need technologists or economists, but motivated system thinkers with soft skills, who are actually prepared to accept responsibility. More than is currently the case, the needs of the business community must furthermore be taken into account in education programmes. This does not mean that the education sector, in developing its education programmes, should exclusively be guided by what companies are asking for. Geert Mol pointed out that this is in fact impossible anyway: ‘We must educate people for professions that may or may not exist in the future.’ Rop Zoetemeyer emphasised the unique role of the education sector in terms of taking initiatives in areas that the business community does not yet recognise for their value. ‘For example, take the biotechnology subject: this was initiated by the education sector and later adopted by the business community.’

The conjecture ‘insufficient use is being made of testing and training facilities’ developed into a discussion about the reticence of companies to put their intellectual property (IP) at risk. Nico Osse has had a bad experience with this and ‘definitely’ does not want to collaborate with test centres and knowledge institutes. Rop Zoetemeyer, former CTO at Corbion Purac, considers this fear unfounded because it is easily possible to contractually specify what forms part and what does not form part of the IP. ‘We do this within the Biobased Delta in a way that makes this feasible.’ This can also result in refreshing new ideas and insights. ‘Without that cooperation, Corbion never would have become as large as it is today.’

According to Bart Wuyts stimulating innovation also is a preoccupation of government. For example, this is already happening in the construction industry, historically a rather traditional sector with low margins: ‘The Belgian government demanded a stricter energy performance level from us, without telling us how to accomplish this. As a result, there was no debate. This led to a catch-up phase that has resulted in tremendous innovations in the energy efficiency domain.’

Teaching Modules

One of the conjectures was as follows: ‘The teaching modules developed within the BBE initiative are only being used by the parties involved in the project.’ To make these teaching modules broadly available, they can easily be downloaded via a digital knowledge platform. They contain fully prepared lessons, which make it easy for instructors to teach their students something about the biobased economy. However, the challenge is to draw the attention of the thousands of educators to these teaching modules. This will become one of the tasks the CoE-BBE will assume in the wake of the BBE project, says Han van Osch, Portfolio Manager Education at HZ/Centre of Expertise Biobased Economy (CoE-BBE).

He briefly described the BBE’s results achieved over the course of the project. One of the most important results is that the people who are active in the education sector on both sides of the border have come to know and trust each other. There now are teachers who are teaching at other knowledge institutes and who were involved in the jointly developed teaching materials. Hasselt University has developed a post‑graduate programme where instructors from other institutions are teaching who have found each other thanks to the BBE project. In addition, there were student exchange programmes, such as a joint programme at a brewery in Flanders, where students from the ]Avans[/anchor and [anchor id=359933]HOGENT universities of applied sciences investigated the reprocessing of residual flows in order to increase their value.

CoE-BBE is going to intensify its cooperation with HOGENT and is even thinking in terms of expanding into an International Centre of Expertise Biobased Economy. ‘That would be a wonderful result of the BBE project.’

Let’s keep meeting each other

The digital knowledge platform contains the contact details of biobased experts, information about research facilities in pilot plants and application centres, traineeships and Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) for students and complete teaching modules for education at various levels. This will ensure that the work accomplished by the BBE project continues to live on. Van Osch admonishes that the digital availability of information does not mean that personal meetings have become superfluous. ‘My experience is that downloading teaching materials from the internet is not sufficient to make things work. Make sure the instructor who taught the lessons in question is known and that he/she transfers it to the instructor who also wants to teach the material. Cooperation is more than an online story. Let’s keep meeting each other, just like we are doing today.’

According to Van Osch, the knowledge platform is furthermore going to play a central role in the continued growth of the biobased knowledge exchange. ‘In the Netherlands, we have a national biobased knowledge network in which 14 universities of applied sciences work together with senior secondary vocational education institutions (MBOs) and share knowledge. This network will be making use of the platform. This enables lecturers to give thought to research questions, and teaching days will be organised. Institutions in Flanders can also join this network.’

‘In addition, we are looking for affiliation with URBioFuture: a Bio-based Industries Joint Undertaking (BBI JU) project financed by the Horizon-2020 programme, with which VITO is also affiliated.’

‘Another subsequent step is the European Educational Community of Practice Biobased Economy: a European knowledge network. In addition to instructors from the Netherlands and Flanders, instructors from Germany, Finland, the Czech Republic and Greece are also involved. The plan is for this to be expanded to include 23 countries and at least 52 knowledge institutes. You can be sure we will be hearing more about this!’

This article was written in cooperation with Biobased Delta

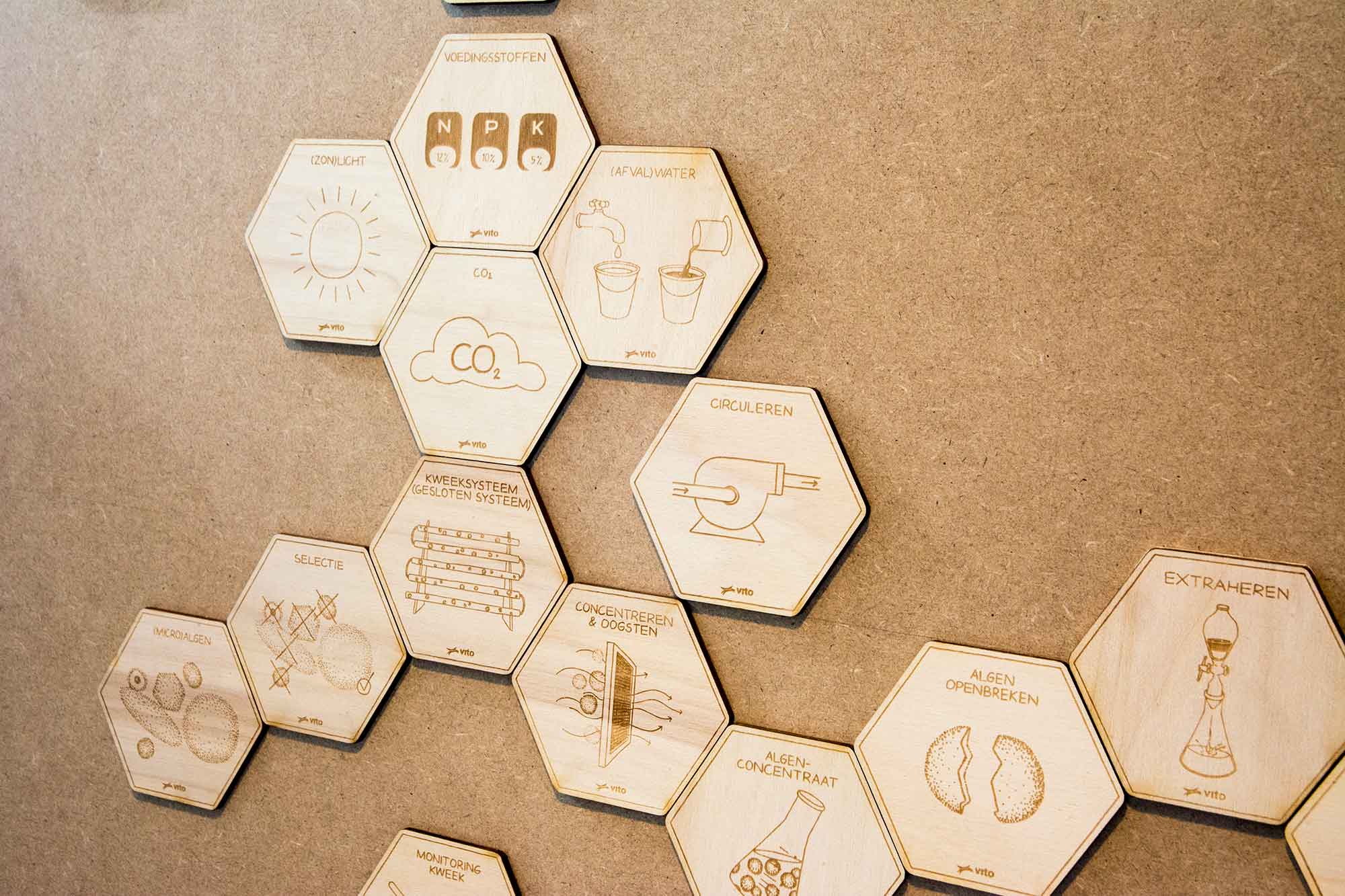

Discussions about new biobased value chains quickly get bogged down in the details, whereby it is easy to lose sight of the big picture. To increase the results-oriented focus of the discussions and to ensure they proceeded in a more constructive manner, the BBE partners VITO and Hasselt University developed the

Discussions about new biobased value chains quickly get bogged down in the details, whereby it is easy to lose sight of the big picture. To increase the results-oriented focus of the discussions and to ensure they proceeded in a more constructive manner, the BBE partners VITO and Hasselt University developed the  A nice overview of the three years of the BBE project is available in the print and digital version of the

A nice overview of the three years of the BBE project is available in the print and digital version of the