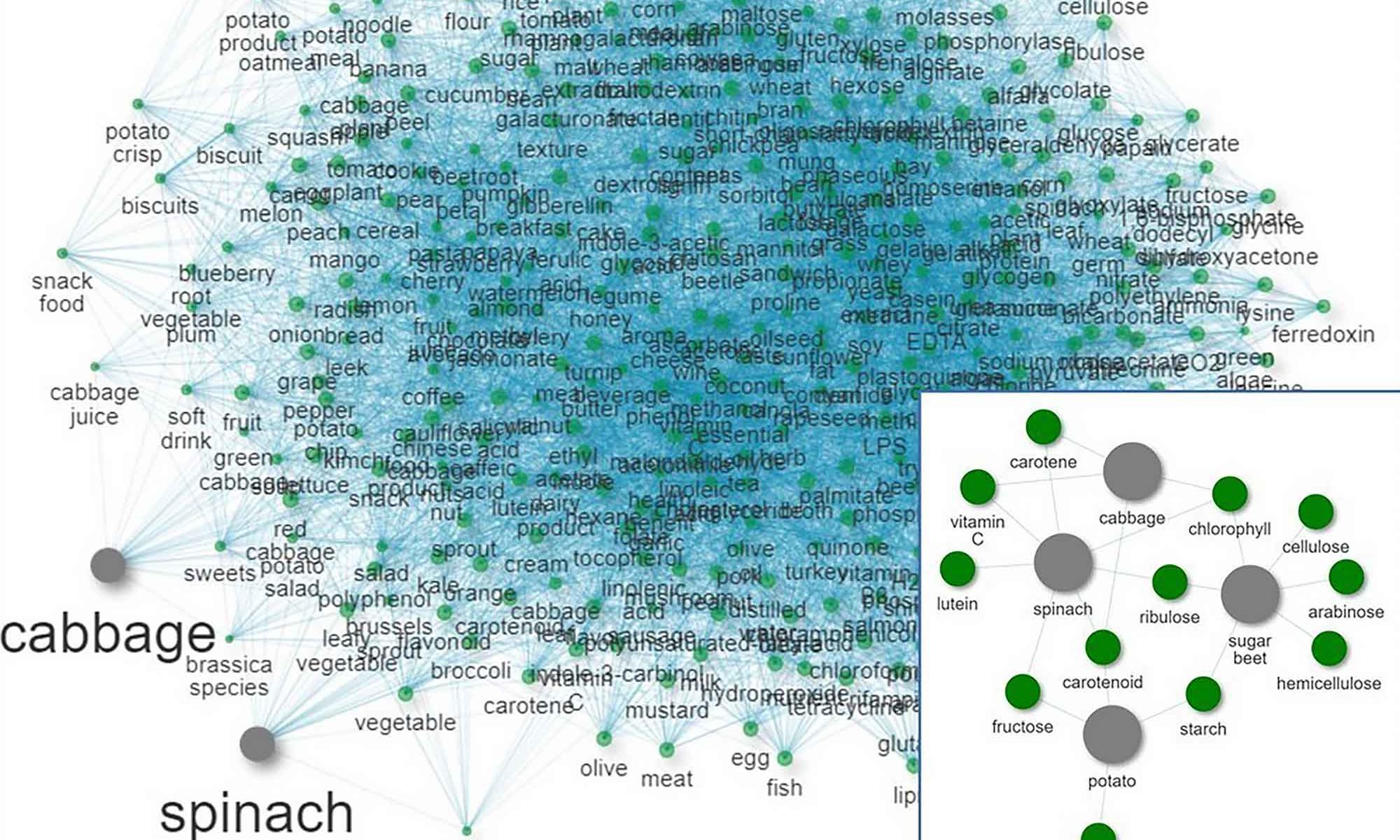

“We were asked by companies if we could do something with the enormous amount of data available,” says Wynand Alkema, lecturer in Data Science for Life Sciences and Health. He led the project together with lecturer-researcher Fenna Feenstra from the Research Centre Biobased Economy (RCBBE) at Hanze University Groningen. “It concerns millions of recipes in open access databases on the internet, but also proprietary information about ingredients. We were looking for a way to make more efficient and effective use of these, by applying smart algorithms to establish relationships between data from all those databases. So it’s basically a search engine, where you start with an ingredient, a recipe or a molecule. You get suggestions about the role of these molecules and ingredients and what other molecules and ingredients they might be replaced by.

In this way, answers to questions such as:

- how can we find cheap and sustainable substitutes for ingredients in recipes and products?

- How can we switch from animal ingredients to plant-based ingredients without losing important elements such as taste and texture?

- How can we promote new combinations of ingredients to make healthy food that consumers like?

However, properties such as sustainability, cost price and availability of an ingredient are not in the database, nor is the preparation method. “We show which molecules are in an ingredient and what its flavour profiles are,” says Feenstra. “We are not going to recalculate how replacing an ingredient changes the mixing ratios with the other ingredients in a recipe, for example. We only indicate what are plausible alternatives for a certain ingredient with the aim of experiencing a certain texture, smell and taste sensation.”

Millions of data

What is the added value of AI in this case? Feenstra: “Everyone has known for years how to search databases, but our AI algorithms search for relationships in a network with millions of data. Not just once, but a hundred times in a row. And at lightning speed. That is impossible for a product developer to do. And it can sometimes lead to unexpected solutions.

Alkema: “That way you find new ingredients to put into a recipe that you wouldn’t have found otherwise. We can use AI to generate plausible predictions for ingredient substitutions time after time. It gives you, as a product developer, a lot more ability to find things.”

Ingredient Maps certainly doesn’t make product developers redundant. “They know best whether such an alternative is more sustainable or cheaper or has other properties that are important in industrial recipe preparation. There are many aspects that play a role in the composition of a recipe. Just look at the recalculation of nutriscores: how nutritious is the whole recipe if you replace an ingredient? Or look at the sourcing: if the ideal replacement ingredient has to come from the Ukraine, for example, you’d rather choose a different alternative. Ingredient Maps does not contribute to these kinds of considerations. We are however looking at possible further development, for example to also be able to display the nutrient values.”

Future

Ingredient Maps is now complete and has already produced several valuable results. However, the forecasts made on the basis of Ingredient Maps are currently only accessible to Hanze University and the business partners. Alkema: “To keep this tool up to date and useful, it needs to be constantly maintained and improved. But making a robust software product based on which companies make commercial decisions is a profession in its own right, and not something the RCBBE normally does. So we are still thinking about ways to open up Ingredient Maps to third parties, for example on a licensing or consultancy basis.”

Companies interested in Ingredient Maps can contact RCBBE.

This article was produced in collaboration with Hanze University Groningen.

Image above: RCBBE/Hanze University