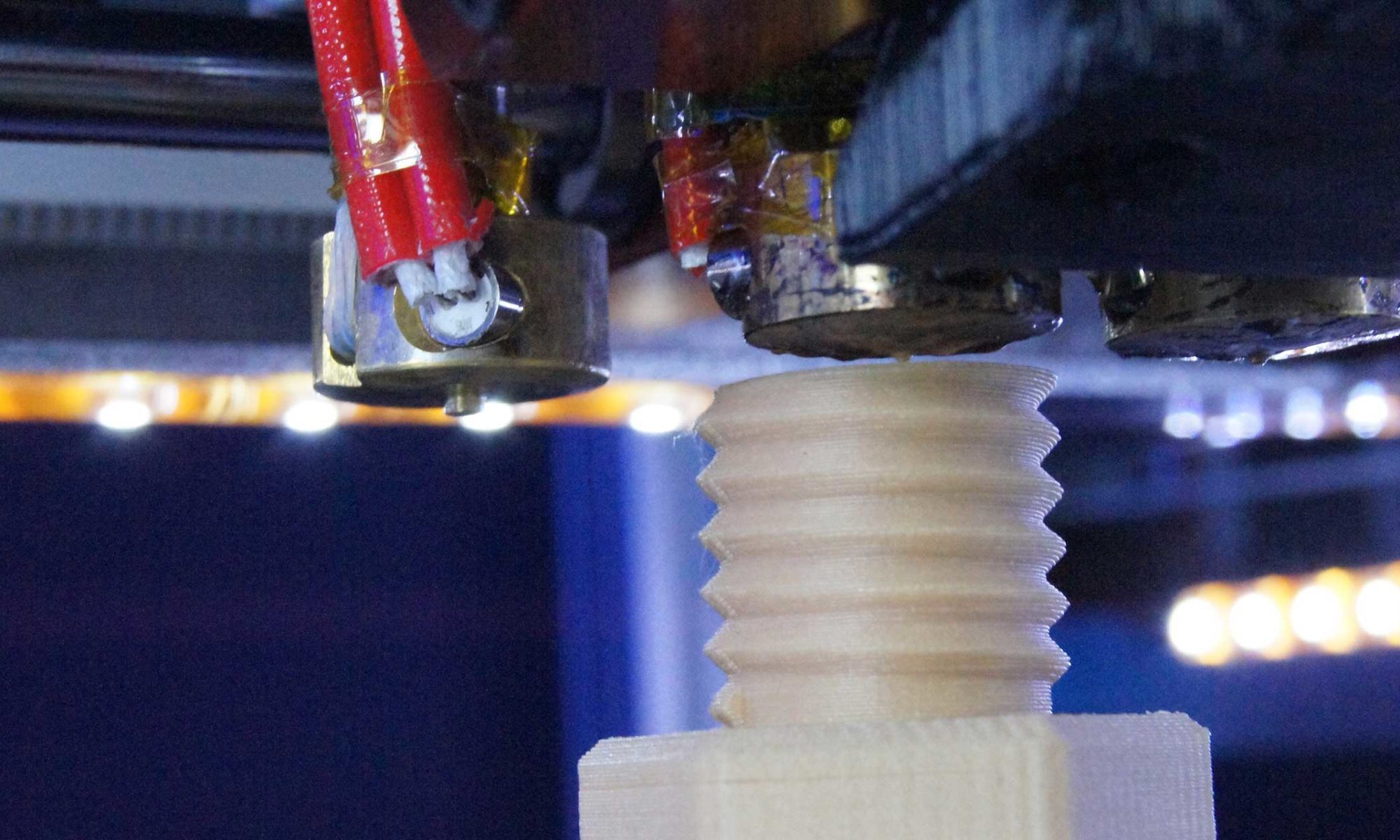

3D printing and micro-injection moulding are high-precision manufacturing techniques. They have in common that they work with thermoplastics: plastics that soften when heated. 3D printing is an additive technique in which objects are built up layer by layer. It is a slow production method, especially suitable for single pieces and prototypes. In micro injection moulding, the polymer is injected into a mould through a small nozzle. This technique is faster, delivering higher mechanical strength and is especially suitable for serial production.

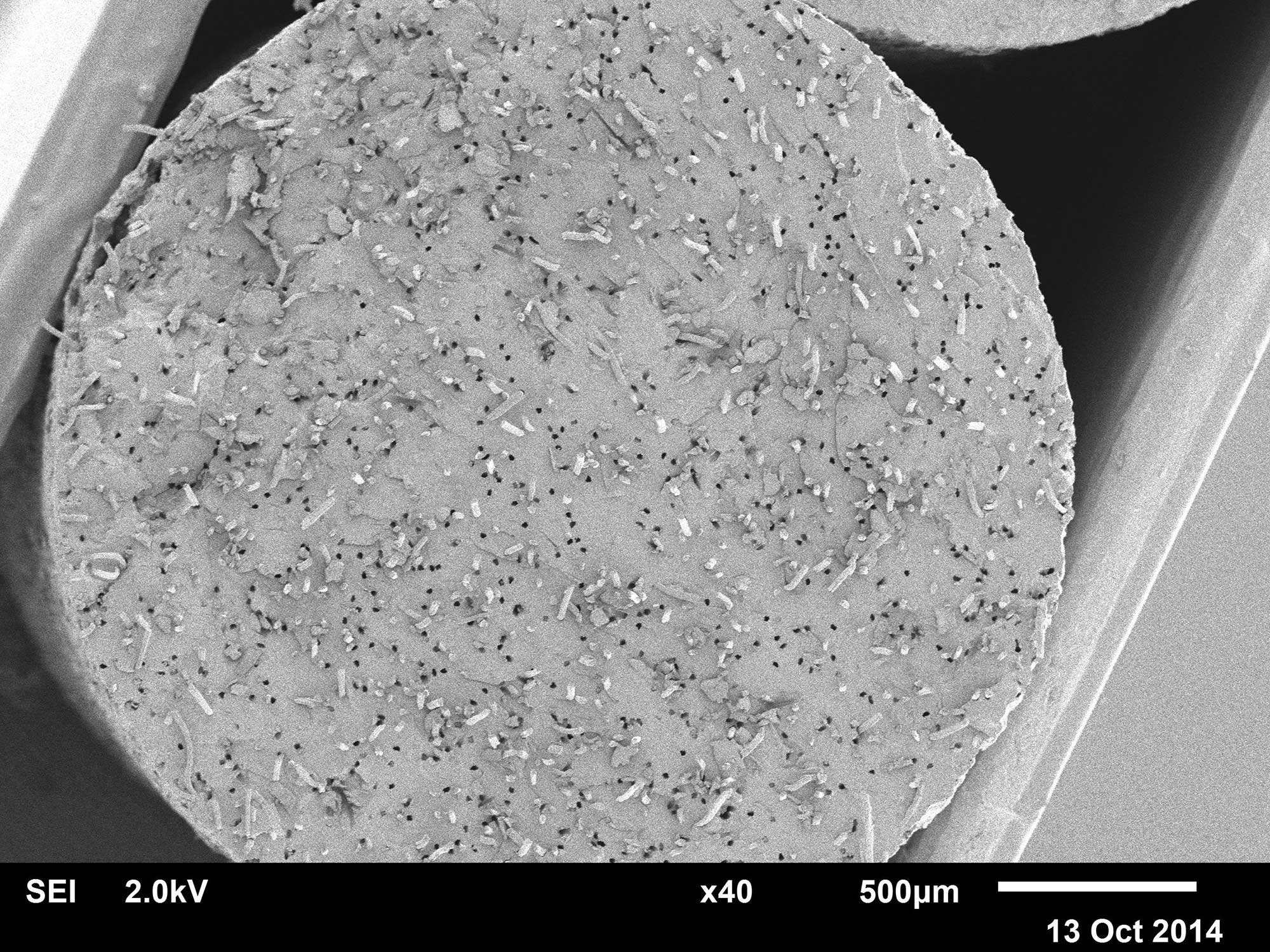

In addition to mechanical strength, flexibility of the materials is also desirable. “The addition of fibers ensures that the material become stronger and would not break in the printer,” says Hansjörg Wieland. He is project coordinator of the 3N Kompetenzzentrum Niedersachsen Netzwerk Nachwachsende Rohstoffe und Bioökonomie in Werlte (Germany). “The biopolymer and the fibers are dosed and mixed in a compounder and granulated. The granulate can then be used in a micro injection moulding machine. Or by means of an extruder a filament is made for 3D printing. In that case, a different composition is necessary. This has to do with the melting point and the crystallization rate. For micro injection moulding, the amount and size of the fibers is limited; the nozzle is very small.”

Green fiber

Which natural fibers are suitable for these techniques? Wieland: “Initially, we looked at horticultural fibers, such as tomato plants, grass, wood and hemp, as well as sugar beets and peas. Currently we mainly focus on cotton fibers from residual flows from the textile industry. These are very thin cellulose fibers with a length of 5 to 6 centimeters. We also use wool fibers, a residual stream from the yarn spinning mill. And also silk fibers; these are protein fibers with a length of about 10cm. Our research focuses on determining how different all these fibers behave when we use them for 3D printing.”

Not all equipment is suitable for processing such long fibers. 3N has a machine for this, but the Dutch consortium participants Millvision and NHL Stenden in Emmen can only use microfibers. Both variants are being investigated within the projects 3D printing and micro injection moulding.

According to Wieland, cross-border cooperation between German and Dutch organizations is going well. “We complement each other well thanks to a wide range of expertise and facilities. Millvision supplies the fibers, 3N and NHL Stenden make these into compounds and produce the filaments. NHL together with HP Moulding has made a computer model to calculate the shear forces and produces so-called tensile bars, which are used at the Hochschule Bremen to test how the material behaves under realistic conditions, under physical stress. From these test results we can deduce for which applications the material would be suitable. Our project partner IST-Ficotex supplies materials and helps us with information about the polymer/fiber mixtures.”

Promising

Promising results have been achieved in both projects. For example, the biobased 3D printer filaments were awarded second prize last year in the Bre3D Award competition in Bremen, in the raw materials and materials category. The jury was enthusiastic about the workability and mechanical properties of these filaments, which would be even better than those of commercial filaments made of ABS or wood. The new materials and the new printing technique (hierarchical arrangement of reinforcement elements) can be used for special applications like parts of film projectors and wardrobe hooks.

The limited availability of PLA and PHA in Europe also plays a role. “The bulk comes from America or Asia. Large companies buy up everything here. As a result, there are shortages here and prices rise even more for smaller companies. This may change, because the worldwide production of PLA is already rising about 15% per year; now more than 1 million tons are produced per year. This will eventually lead to a price drop.”

According to Wieland, companies will also be willing to pay an additional cost for high-quality products, where degradability is of decisive importance. “We think that our materials can be used in applications where there is a risk that microplastics would end up in the environment. Together with a company we have developed a special compound for agricultural machines with many external, rapidly wearing parts. At the moment the material will be tested. Another product which were developed are coffee cups from PHA produced by HP Moulding.”

“Building on our experience with renewable materials in the project we produce at the moment mounts for face shields against corona infection from biopolymers and natural fiber reinforced biopolymers by 3D-printing and injection moulding. These shields are distributed to rescue services, retirement homes and medical practices for free.”

This article was written in cooperation with Ems Dollart Region (EDR).