Two relatively young businesses chose for Chemport Europe because of its good infrastructure and networking possibilities: BioBTX and Enerpy.

‘Fertile environment’

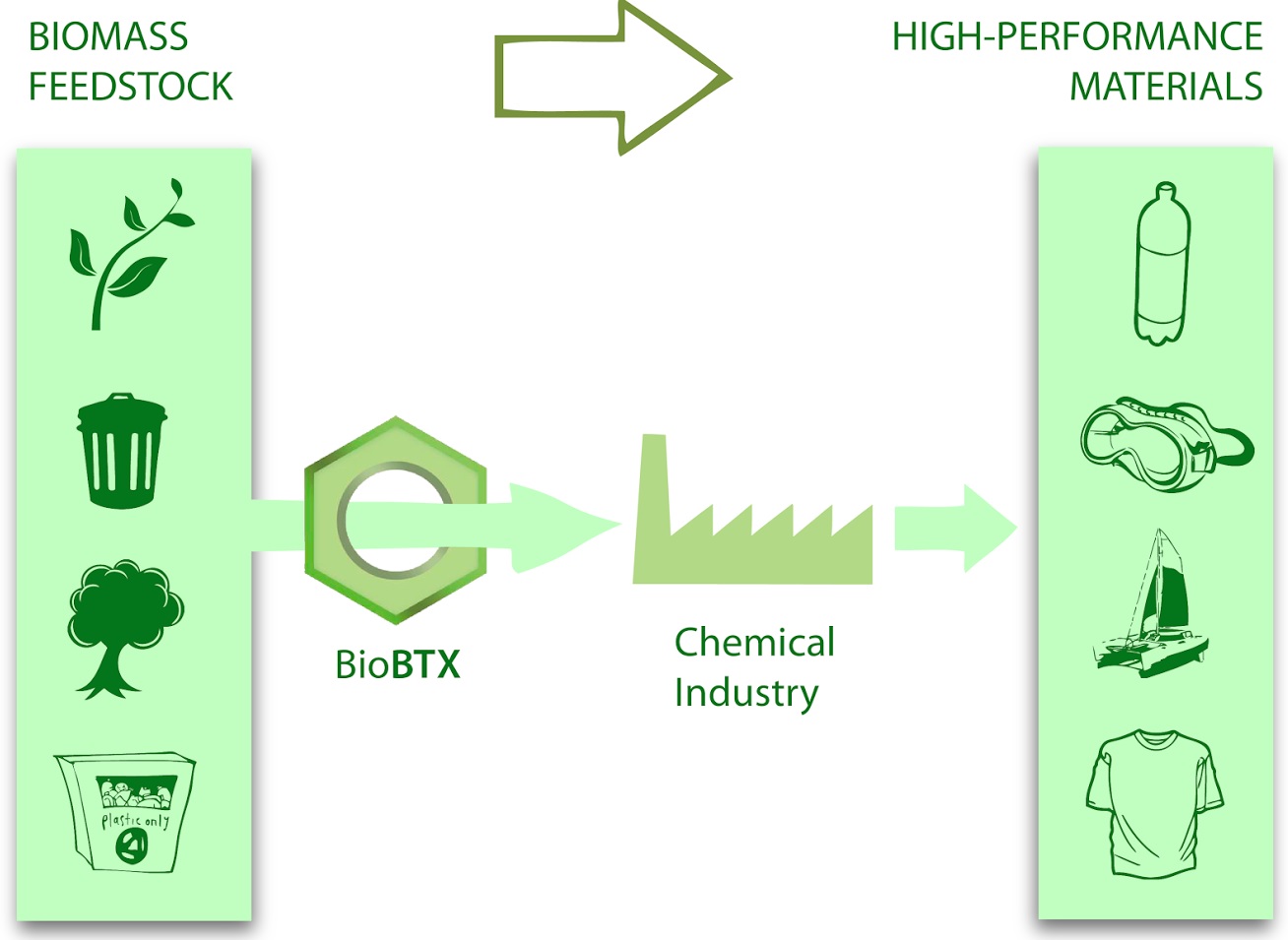

BioBTX is a familiar name for readers of Agro&Chemistry. The company converts biomass and residual streams into chemical building blocks, such as those also used in the petrochemical industry: benzene, toluene, xylene and other aromatics. BioBTX will open a pilot plant in the new ZAP building at the Zernike Park in Groningen in June this year.

‘We are very much geared towards the north of the Netherlands,’ says Pieter Imhof of BioBTX. ‘This is a fertile environment for developing and scaling up bio-based technology. We work closely together with the University of Groningen and Syncom, and our laboratories are also located at Zernike Park. Now that we are going to operate a pilot plant in ZAP, the entire infrastructure required is being organised for us. The province and municipality are also ensuring that permits are handled thoroughly without any hiccups.’

From waste to building blocks

In the first instance, BioBTX will use the pilot plant to extract building blocks from liquid biomass, and later also from contaminated plastics or plastic composites. Imhof: ‘Originally we focused very much on biomass, but now we also target end-of-life materials that can otherwise not be processed further. Pure plastics simply can and must be recycled and put to use again. But if plastic is contaminated, has been incorporated in a composite or contains several layers on top of each other, it is difficult to separate. Usually all that can be done is dump or incinerate it. Yet, with our technology, we can convert the plastics back into basic building blocks, the same way we do it with biomass. In that sense, we do really contribute to the circular economy.’

The technology has already been proven to work on gram and kilogram scale, which led to the first bio-based cosmetics container (in collaboration with Sunoil, Syncom and Cumapol). ‘But this scale is too limited for making the jump to commercial production straight away. That is why we are building this pilot plant. We will be able to use it to carry out more extensive tests and run batches for potential customers. The plant has a capacity of 10 kg/hour for feed and a couple of kilograms material for output.’

According to Imhof, the technology is already commercially viable now. ‘We are in discussion with a number of interested parties. This concerns building slightly smaller plants that match the volume of waste processing precisely. In that case you are talking about 10 to 50 Ktonnes of materials. The resulting products can be processed further in existing plants.’

Radiolysis demonstration plant

Enerpy is a newcomer in the north. This spring, the business from the rural Renswoude (Province of Utrecht) will move with its demonstration plant to the Eemshaven. This technology is related to pyrolysis, but with higher yield because the energy-guzzling convection and conduction are largely excluded. ‘We use a high-frequency wave which allows our plant to crack molecules with a considerable energy load,’ says Jos Koopmans of Enerpy. The result: oil, carbon and gas.

The company already built a demo plant in 2015. ‘That was an innovation project for us to get from proof of concept to industrial scale. It allowed us to increase our capacity all at once from 80 to 500 kg/hour. We are satisfied with the results and have shared them with various parties. Now we are ready to professionalise our plant and enlarge it. Not just in a farm shed, but at a location where we can share our knowledge and expand our network.’

‘We fit in with the network’

The plan in the first instance was to move to the port of Rotterdam, but it was not possible to find a suitable location there in the short term. Via iTanks, the knowledge and innovation platform for port-related industry, Koopmans ended up in Delfzijl. ‘In consultation with Seaport Delfzijl we found a location we are keen to shift to. Not that we need a port, but you often find several chemical companies at ports and they will be our partners for the coming years. We work together with ECN and the University of Groningen and see that heat, steam and carbons are in demand in the area. We fit in well with that network.’

At this location Enerpy will also carry out tests with Renewi (the merged company of Shanks and Van Gansewinkel) with various waste streams. ‘I anticipate that in a few years we will have a plant that can upgrade organic residual streams on industrial scale into aromatics for the chemical industry. That is in fact our aim. So specifically we are examining residual streams that cannot yet be recycled, as BioBTX does. We may possibly form a consortium for this purpose, in which the University of Groningen, Renewi and Port of Groningen could be potential partners we would be happy to work with. It is a way for us to link up with the Groningen network.’