Circular Biobased Delta (CBBD) has therefore embraced chemical recycling as an integral part of the green transition. “Accelerating the raw material transition through biogenic routes and finding circular solutions is our goal. In doing so, our focus is on green chemistry and chemical recycling,” said chairman Willem Sederel this week during CBBD’s online network meeting on chemical recycling.

With the establishment of the South Netherlands Pyrolysis Testing Ground, the region, together with the Port of Moerdijk, had already been at the cutting edge of chemical recycling around 2015. Since then, developments in the region have accelerated: Shell’s investment in pyrolysis technology to supply the company’s crackers with bio-based naphtha within a few years, the plans for the construction of a chemical recycling plant in Vlissingen and the start of the PyroChempark project. Sederel also mentioned a number of trans-regional developments, such as the establishment of the Chemical Recycling Network earlier this year and the submission of a National Growth Fund proposal to stimulate material innovation through green chemistry and chemical recycling.

Meanwhile, it is also clear that the landscape of chemical recycling is becoming increasingly diverse, with a range of technologies (solvolysis, depolymerisation, pyrolysis, gasification, etc.) and feedstocks, from biomass to waste plastics and car tyres. Which ones are promising and where do the companies stand on the road to commercialisation? CBBD mapped this out with a technical-economic analysis, which was explained during the meeting by Marcel van Berkel. The detailed analysis is available to all members of the Chemical Recycling Network and highlights issues such as CO2 reduction, market pull, dependence on gate fees and profitability, but also the complexity of the technology, availability of raw materials, scalability and required investments.

Key note from Shell

The chemical industry is now convinced: chemical recycling is the way of the future. Shell alone has the ambition to recycle 1 million tonnes of plastic waste worldwide by 2025. It can be converted into bio-naphtha, from which the company can make new plastics such as PE, PP, PS and rubber in its crackers. Shell recently signed a contract for that with technology provider BlueAlp.

Vincent Baril, president of Shell France explained the plans and challenges during the CBBD meeting. “We need to move quickly to larger volumes, but also pay attention to upgrading the product before we take it to the cracker.”

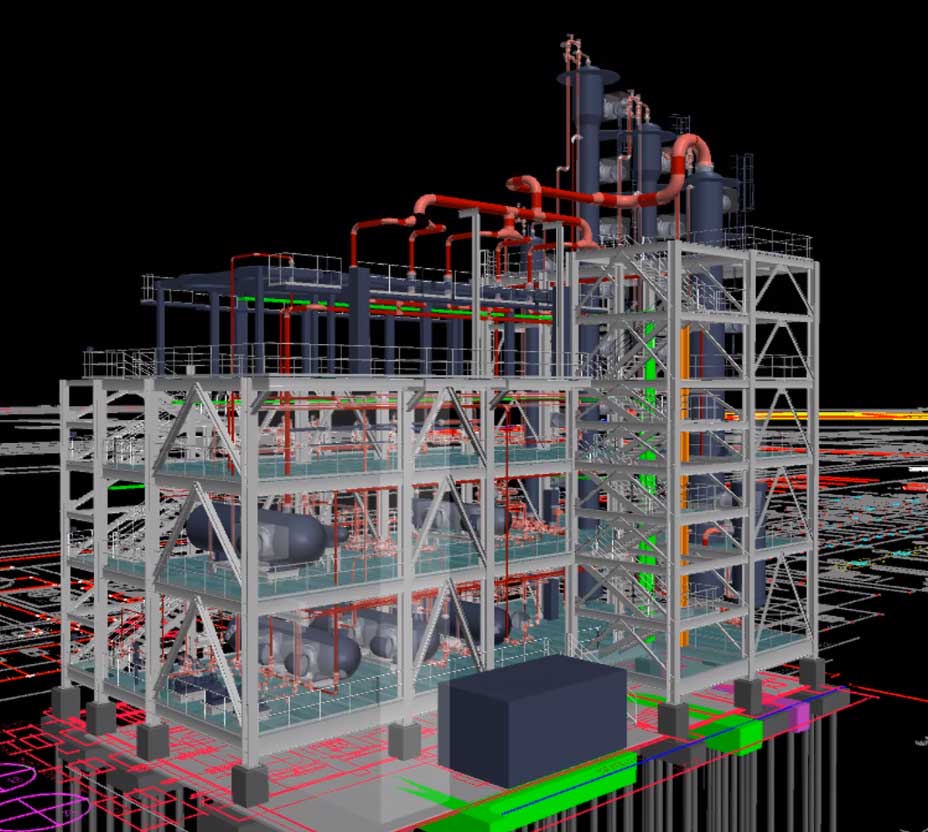

After all, this is often still a forgotten step. Pyrolysis oil contains impurities. Cleaning and upgrading to a pure product will be necessary at all times. Shell is developing its own technology for this and will apply it on a large scale in an initial project in Singapore: a 50 kt upgrade plant, which Baril says will be “the tipping point for large-scale recycling.”

Why will the plant be located in Singapore? “Because it is easier to set up there than elsewhere in the world. Europe lags somewhat behind other countries with regulations to enable rapid scaling up.”

Raw materials

The purity of a product like pyrolysis oil depends not only on the technology, but also on the quality of the raw materials. Waste processors notice this. Kim Meulenbroeks, manager product development of Renewi, observes that the input specifications of recyclers differ considerably. “In pyrolysis alone we are dealing with five or six different types of input specifications. We need more standardisation, or else it may be difficult to move towards larger streams.”

Another development Meulenbroeks sees is that the requirements for the quality of input streams for chemical recycling are getting higher and higher, so that chemical and mechanical recycling are even starting to compete with each other in the battle for ‘clean’ waste plastics. This requires more intensive sorting, which drives up costs, if only because material is lost at each stage of the sorting process. She concludes: “The winners of this technology will be those who do not have too strict input specifications and who can deal with a contaminated source.”

Indispensable option

So is chemical recycling the Holy Grail of the circular economy? That is overstating the case. It is a promising option that helps to increase raw material security and reduce the industry’s carbon footprint, along with mechanical recycling, the increasing use of bio-based raw materials and the energy transition. At the same time, it is an option that is indispensable, will continue to develop and will provide many economic opportunities in the years to come.

This article was written in cooperation with Circular Biobased Delta.