Degrowth should save the world. Egbert Dommerholt, Professor of Biobased Business Valorisation at the Research Centre Biobased Economy/Hanze University Groningen (RCBBE) is convinced of it. Continuing to strive for economic growth and raking in as much money as possible is a dead end. Other values must replace the pursuit of monetary gain. Economist Jason Hickel wrote as such in his book ‘Less is More – How degrowth will save the world.’

“We will have to upgrade our values,” says Dommerholt, who in recent months led five meetings at the Hanze University of Applied Sciences where specialists gave their views on degrowth, in the fields of science, business, education, society and legislation. “With these, we have initiated the discussion. What is still missing is the notion of where we are going. What kind of economy do we really want? And how do we get there?”

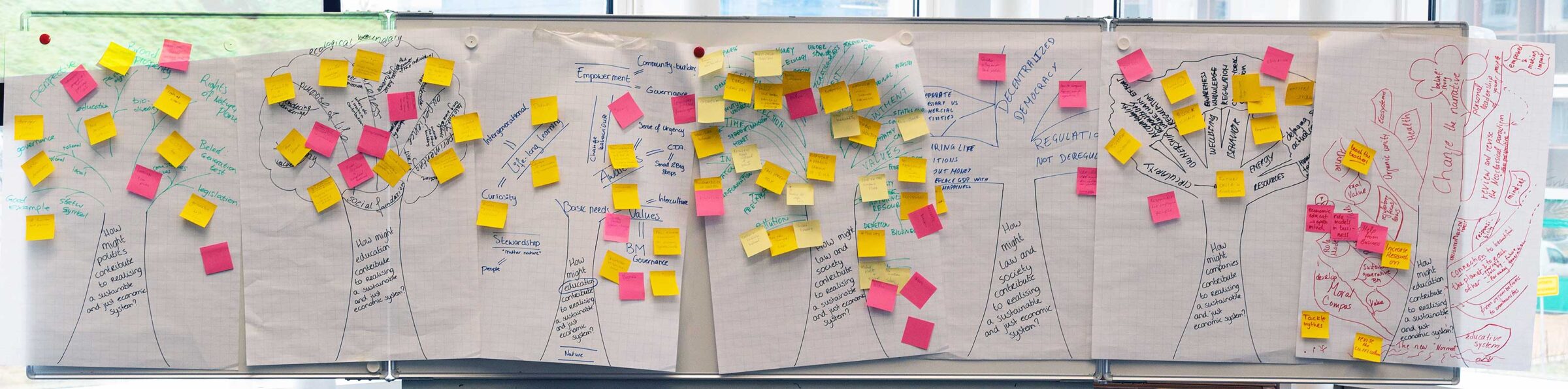

A final brainstorming session was held with a handful of forerunners in the field. It was intended to bring clarity to this issue. Led by communications professional Marrit Nijdam, teams from different disciplines were brought together: economists, education professionals, as well as lawyers and entrepreneurs. They worked out the key issues in order to find practical handles for the right path to degrowth.

Key

Education is an important key to those changes: “That is also the reason why I am into education. If you want to change the world, it starts with young people. They are the workers and managers of tomorrow. This is where it has to start. We as educators do not have the definitive answer to all questions, but we can set an example and help them get started.”

More support for the degrowth mindset, which sometimes seems contradictory to entrepreneurial interests, is gradually emerging from the business community. For example, Elske Doets of the Dutch travel agency Doets Reizen is trying to get people to book fewer long-distance trips. As a result, she is seen as the black sheep in the travel industry. A lot of large multinationals also regard profit maximisation as their main goal. They will only address sustainability issues that contribute to that goal. Other, more socially important but less profitable goals, such as ending hunger (SDG2), are not addressed. Creating shareholder value still plays a bigger role in the industry than meeting climate goals. ” It clashes. Hopefully that will change, because we have to remember that we are living together on one big planet.”

On top of that, wealth on this planet is unevenly distributed. In African countries, degrowth is looked at as a luxury concern. “A student once pointed that out to me: our people are hungry, they have completely different worries on their minds.”

‘Nothing comes from above’

So what then is the solution? “We act as if the current economic system came out of thin air, but it didn’t. It just evolved. The question is where we are going next and who is going to lead that process.” Dommerholt is not expecting much from politics. “Politicians in The Netherlands are currently bouncing from crisis to crisis. Hardly anything comes from the top down. For instance, government is proclaiming that the Netherlands must be fully circular by 2050, but not how to achieve it. The laws and regulations are not designed for this at all. And it’s not going to happen by itself.”

In fact, of course, government is part of the same system in which growth and making money are central. It levies taxes on labour, profit and value added. There is no incentive to reduce growth. “If we are really serious about the resource and carbon issues on our planet, we have no choice but to change the way taxes are levied. For example, by taxing CO2 emissions from individuals. In doing so, the income tax you pay is determined by the amount of carbon emissions you are responsible for through your consumption. The more carbon, the higher the rate. Companies will understand that it is no longer just the price of their products, but especially raw material use and CO2 emissions that are important competitive factors. They will have to put fewer or different raw materials in their products if they want to keep their patronage. We need politicians to make this happen. But it can be done.”

According to Dommerholt, this is the only way forward. And bottom-up, community-based pressure is absolutely necessary in this regard. “Therefore, democratisation absolutely has to go much further than what we have now in this country. Consider democracy at the citizen level or maybe even at the product level. It’s all possible, without losing power. Just: do it! That’s a stone I want to cast into this pond.”

The sequel

The outcomes of the degrowth lecture cycle and the brainstorm have been captured in a report. But it won’t stop there, if it is up to the RCBBE. Egbert Dommerholt advocates setting up a Degrowth Community or joining existing movements, to keep the momentum going. The community could make use of the expertise present within Hanze University as well as the involvement of enthusiastic young people. During bi-monthly meetings, insights, updates on projects and ideas for sustainable action could be exchanged. Such meetings could also be used to organise joint actions, such as writing open letters, proposals and manifestos with proposals for education, research, business and governments. Question times and joint research projects are also an option.

Want to know more about degrowth and the initiatives from the Hanze University? Contact Egbert Dommerholt or Sanne de Boer.

This article was created in cooperation with the Research Centre Biobased Economy of Hanze University Groningen.