‘The European Green Deal is our man on the moon moment.’

But first, the European Green Deal. It would be too much to cover it in detail here. It is a kind of Marshall Plan – the European Recovery Plan after World War II – but then many times larger in terms of investments and elapsed time. ‘It is our man on the moon moment,’ asserted Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission.

It was the challenging task of Frans Timmermans, Vice-President of the European Commission, to come up with a master plan within 100 days. The European Green Deal was presented at the end of 2019. The Green Deal Investment Plan and a Transition Plan (to finance the costs/implications of the transition) followed several weeks later.

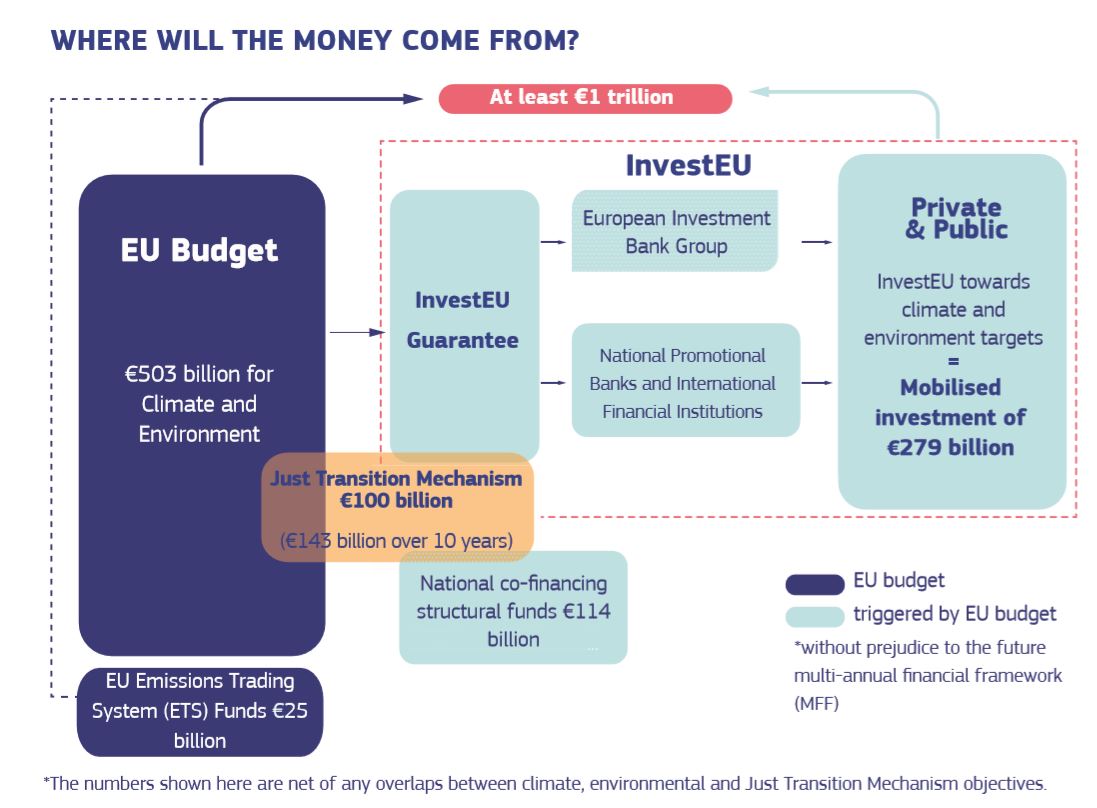

To give an impression of the funds that will be freed up over the short term (2021-2030): €1,000 billion for sustainable investments and €100 billion for ‘transition support’. See Figure 1 for a diagrammatic illustration.

Interim progress report

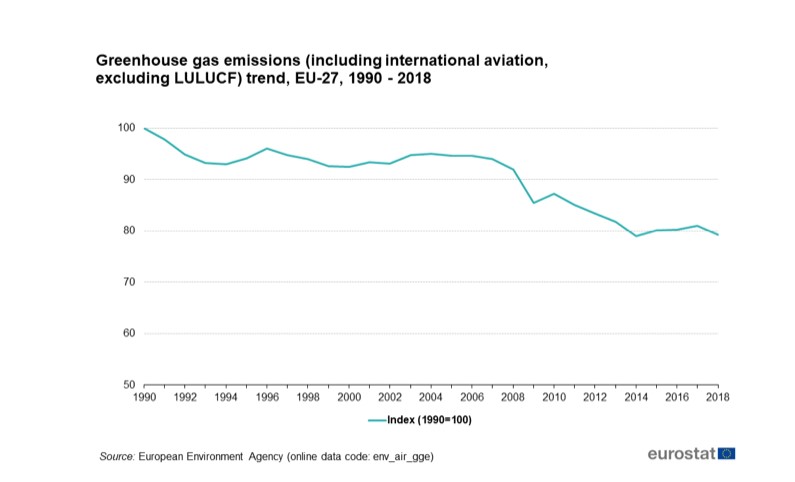

Ultimately, the European Green Deal is to result in significant reductions in CO2 emissions in various sectors over the medium term (2030) and the longer term (2050) (see above-referenced policy domains). These goals will be incorporated in the Climate Act that the European Commission presented in March 2020. Currently the target for 2030 is a 40-percent reduction (compared to 1990) and zero emissions by 2050. The latter does not imply that fossil feedstocks (energy, chemical industry) will be a thing of the past in 30 years, but that the CO2 emissions will be compensated, for example through means of Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS).

An interim progress report, prepared in 2018 (see Figure 2Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO)) shows that between 1990 and 2018, the EU has reduced emissions to 80 percent of the 1990 emissions. In other words, the EU and most member states are on the right path. Not everyone shares that opinion, however.

The lobby circuit

Over the past few months the European Green Deal was subjected to criticism coming from different directions. Considering the plan’s impact, this is not really all that surprising.

One point of criticism in particular comes from NGOs, namely the fossil lobby’s influence on the plan. The Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO), an organisation that closely monitors the lobby circuit, noted more than 150 meetings between the oil and gas lobbies and members of the European Commission. According to the CEO, the EGD has become partly ‘fossil’ coloured with funds that can also be used for gas as a transitional fuel. According to the CEO, CCS is also not the way to go, because it still allows for CO2 emissions, it is economically unprofitable and is potentially detrimental to the environment (land use, for example) in the regions/countries where CCS takes place.

Finally, the role of (green) hydrogen. The sectors supporting this technology apparently have convinced EU decision-makers of the role this energy carrier can play in the energy transition. Although the EGD focuses on green hydrogen, it is also keeping the door open for fossil resources, such as natural gas, according to the CEO.

Good intentions, but…

Greenpeace Nederland also criticises the EGD, especially the plan’s effectiveness. ‘At the present time the extent to which the EU (member states) will achieve their CO2 reduction targets through means of the Green Deal is still unclear,’ asserts a spokesperson. ‘While the Green Deal contains a number of key reforms and good intentions, we will not achieve what according to science is required to counter the climate and nature crisis. Emissions must by 2030 be reduced by two thirds, not by only 50 to 55 percent. We have to abandon all fossil fuels rather than being overly optimistic about the use of gas. The fact that the Commission is asserting that subsidies for fossil fuels must be stopped is all well and good, but ten years ago Europe also set this goal for itself. But yet there isn’t a single member state that has developed a specific plan for this. This also is the problem with the Green Deal. It is full of good intentions, but it barely contains any specific plans or points of reference for member states to guarantee that they will achieve their targets. The measures it contains are generally weak and/or still need to be worked out in further detail.’

Glass half full

Willem Sederel (Chairman Circular Biobased Delta) considers the criticism of the EGD coming from NGOs premature. ‘In view of the important role of the oil/gas/petrochemical sector, these parties naturally need to be involved in the EGD. However, I am a proponent of adopting a constructive attitude and consider the glass half full. The financial details of the EGD are not yet clear. I expect to see more information to be released about this in September or October. For example about Horizon Europe, the successor to Horizon 2020. For the time being the Horizon 2020 projects will continue up to the end of 2023/2024. Furthermore, the EGD’s content has already been adjusted on the basis of the feedback provided by involved parties and the European Parliament. For example, in May 2020, the Commission presented two strategies as part of the EGD: and new, modified biodiversity strategy and the Farm-to-Fork strategy on food and food wastage.’

‘Technically/economically much is already possible, but the biggest challenge lies in social innovation.’

Sederel is of the opinion that the EGD definitely can contribute to the above-referenced CO2 reductions. ‘Given the timespan – three decades – a lot can happen. Technically/economically much is already possible, but the biggest challenge lies in social innovation. It’s good to see that the EGD devotes ample attention to this as well. It is a precondition for getting the circular economy off the ground. Naturally, the path towards 2050 has not yet been set out in its entirety. There still are some blank spots. The condition that applies to the Netherlands is that in order to achieve its Climate, Raw Materials and Energy Agreement targets, it must set aside its political viewpoints and opinions, and constructively work together on a solution on the basis of facts. The biomass energy debate is a good example of how we continue to talk at cross-purposes otherwise. As a result we run the risk of putting ourselves in an exceptional position in Europe and missing the boat in terms of green jobs and green investments that instead will then go to our neighbouring countries.’

Major impact of the bio-economy

Philippe Mengal, Managing Director of the BBI JU, likewise is cautious with his assessments about the EGD. ‘I do not want to get ahead of the parade. Presently I can only speak for the BBI JU and, as you know, the BBI JU will be restructured to create a new organisation, the Circular BBI JU. The focus remains on sustainably acquired second-generation and (over time) third-generation biomass – as an energy source and feedstock – for bio-refineries. In short, stimulating economic activity that also contributes to biodiversity, an aspect that is included in the EGD as a crucial policy domain. In terms of research, CBBI JU will focus on bio-refining, since bio-energy is already a mature discipline.’

The Bio-based Industries Consortium (BIC), the private pillar of the BBI JU, also expressed its opinion about the EGD and the role of the European bio-economy in this comprehensive plan. BIC hereby emphasises the economic weight of the bio-economy and the impact it can have on economic recovery in the post-COVID period (more about this later). Furthermore, according to BIC, making the primary sector and related sectors sustainable will generate economic activity that will not go at the expense of ecology.

Biomass stays in the picture

Lofty goals that will no doubt generate criticism, for example of the agricultural intensification and the role of biofuels in transport and energy generation. However, in the gradual replacement of fossil energy sources, all options will need to be considered and included. Currently, the share of renewable energy in the EU is still on the low side. In 2018 its use (gross final consumption, Eurostat) was 18.9 percent, and is on its way to 20+ percent in 2020. This percentage no doubt will have to go up significantly to achieve the required CO2 reductions. This applies to all forms of renewable energy. The Knowledge Centre for the Bioeconomy (KCB) of the European Commission argues that biomass plays a key role in energy generation in the EU. In 2016 the share of bio-energy in the renewable energy mix was almost 60 percent (KCB). Moreover, the share of bio-energy, just like other renewable forms of energy (wind), is not growing as fast as expected. Perhaps the EGD can bring about a change in this area.

The corona factor

As mentioned earlier, the importance of the EGD only increased as a result of COVID-19. Where the plan originally was linked to climate and creating a (new) more sustainable economy, today the plan must also pull the EU as a whole out of the COVID-19 crisis. Earlier this year, Von der Leyen explicitly linked the European COVID-19 recovery plan to the EGD. The EC President called it ‘our motor for recovery’. ‘We have to guard against lapsing into old, polluting habits.’

The DSGC (Dutch Sustainable Growth Coalition) shares the same opinion. In June this initiative, an association of the CEOs of eight Dutch multinationals and a Confederation of Netherlands Industry and Employers (VNO-NCW) representative, published a letter in which it calls on the Dutch government to ‘support the European Commission in its intention of incorporating the Green Deal as a core element of the EU recovery plan’.

‘By embracing the ambitions of the Green Deal towards a climate-neutral Europe by 2050, we accelerate the global sustainability transition, which leads to European economic growth, millions of new jobs and a healthier population. The precondition is a level playing field at a global level. We must prevent European business and industry from being outcompeted due to unequal conditions in the field of sustainability.’

‘By 2030, emissions must be reduced by two thirds, not only by 50 to 55 percent. We have to abandon all fossil fuels rather than being overly optimistic about the use of gas.’

– Greenpeace Spokesperson

Too far ahead of the parade?

This last observation is a real possibility and to a high degree depends on the CO2 reduction ambitions of important competing nations/trading partners, such as the US and China. In the US, these ambitions are currently on ice and under Trump the country has largely been pursuing a protectionist policy.

Still the probability that the EU will get too far ahead of the parade and price itself out of the market appears to be small. In a Whitepaper, the Standard Chartered bank emphasises the EU’s market power to impose standards, including sustainability standards, on global suppliers and this way put pressure on local governments to toughen legislation and enforcement.

The bank signals that various countries are following the EU in terms of their ambitions. For example, China has its national plan for implementing the Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development, which includes experimental programmes in the area of social, economic and environmental protection. It has set up sustainable development zones and more than 40 so-called CO2 pilot provinces. According to Standard Chartered, India, another economic superpower in the making, is also implementing leading sustainability programmes.

Finally, separate from the international impact, EGD will also have to get everyone on the same page in its own house. Particularly Poland, which is highly dependent on fossil energy (coal), must still commit itself to the 2030 and 2050 targets. The country is currently hoping for several billion euros from the Transition Fund. To be continued.

Image: Circular Biobased Delta (Nick Francken), Hydrogenious, European Commission, Bio-based Industries Consortium