The API Institute emerged in 2009 from the former research and development department of Diolen Industrial Fibers in Emmen. The producer of industrial yarns, among other things, had various owners, including Enka, AkzoNobel and investment company CVC Capital Partners, before it went into liquidation in 2008.

‘However, the R&D department of Diolen Industrial Fibers saw opportunities for continuing independently,’ says Gerard Nijhoving, who runs the new company together with technical director Bas Krins. ‘This specialist background meant there was a lot of demand for research and laboratory facilities in the field of industrial yarns, but also in polymerisation. We have received more and more enquiries about biopolymers over the past few years.’

The API Institute was able to attract various investors and likewise created the successful spin-off Innofil3D. The production of monofilaments for 3D printers started two years ago in a separate building on the premises in Emmen. Innofil3D has since grown into a leading producer in a market segment with huge potential.

Fit for use

Nijhoving, as a freelance business developer, investigated how the API Institute could improve its business operations. He also examined the opportunities for setting up other successful spin-offs, and concluded that more money was required to invest in this. ‘The shareholders, however, were already fully involved with Innofil3D. So it was obvious that we should split the two companies and continue independently as Senbis Polymer Innovations.’

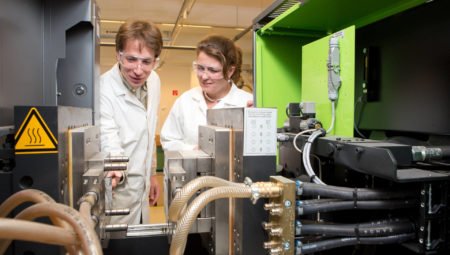

The above company will continue to focus on polymer research and related services. Nijhoving: ‘Clients engage our specialists to solve production problems or test samples. Lately we have been receiving an increasing number of enquiries from polymer producers to make their products suitable for 3D printing. These companies have often already developed grades for all kinds of applications such as injection moulding and blow film extrusion, but want to expand their range for this new market. This making ‘fit for use’ work suits us well, since we also do it regularly for yarns.’

Top region

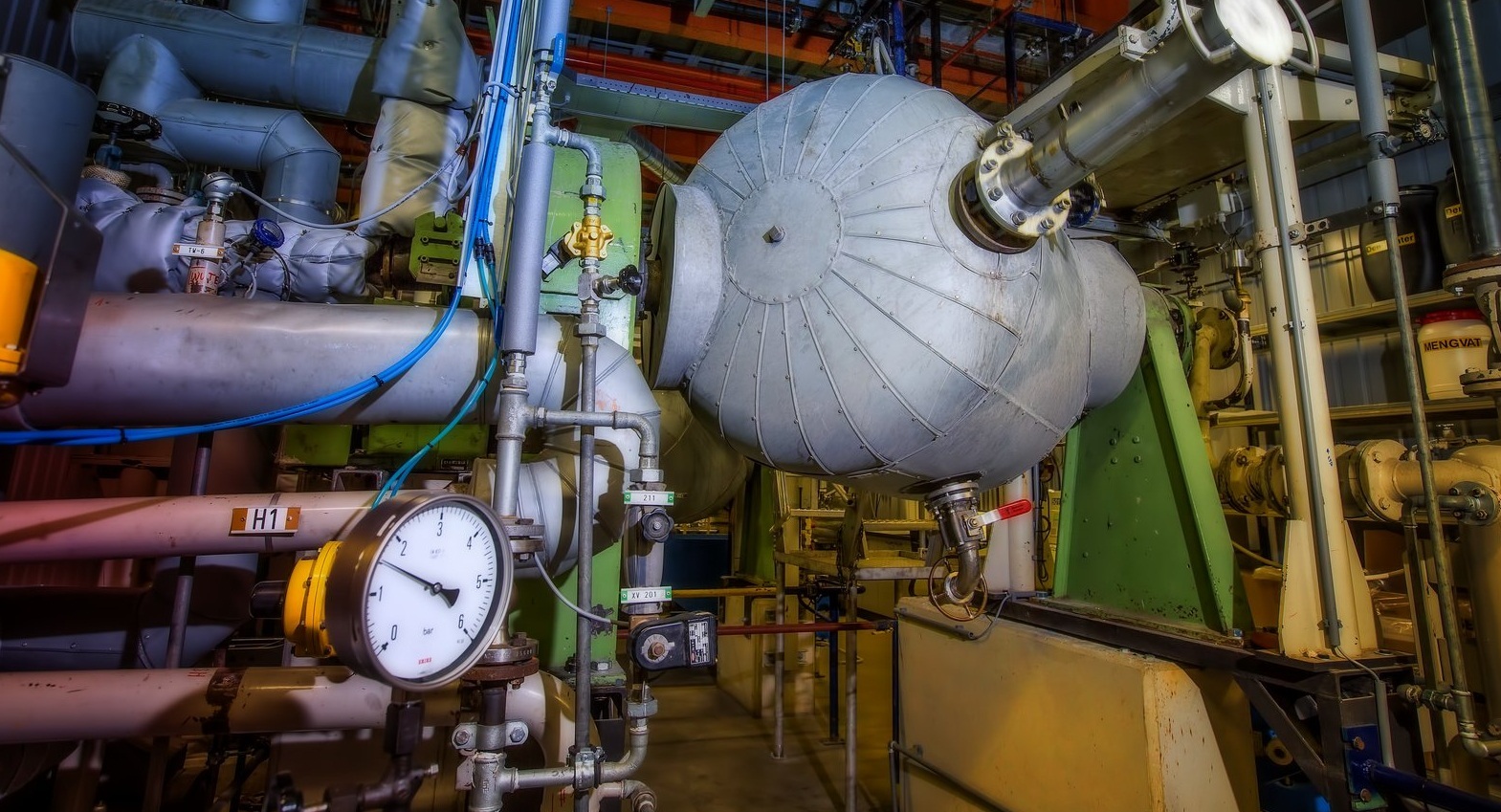

Senbis Polymer Innovations has an extensive polymer laboratory. It contains analysis equipment for rheological and mechanical measurements, among other things. A wide range of processing equipment for polymers is also available, such as three spinning machines for the development of new yarn products. There are also various extruders for making compounds and monofilaments for R&D purposes in quantities of a few kilograms per hour. Senbis Polymer Innovations also has an autoclave for producing new polymers. ‘Moreover, we can call on an extensive network so that large-scale tests can be performed elsewhere if we cannot provide for that here ourselves. Our location here at the Emmtec industrial estate also puts us with big players, such as DSM and Teijin Aramid’, emphasises Nijhoving.

The industrial profile with Emmen as the largest cluster of synthetic fibre companies gives the bio-based economy in the region good growth potential. There is good reason why the government designated Southeast Drenthe as the top region in the Netherlands for vegetable raw material-based green chemistry. In Nijhoving’s view, the team of eight employees share a wealth of experience in polymer chemistry. ‘They are not only scientists, since we also have operators who have gained extensive experience in spinning yarns at Diolen Industrial Fibers and AkzoNobel.’

Compostable horticultural twine

The new co-owner realises that a pilot plant and laboratory facilities are often too expensive for SME companies. ‘In offering our facilities, we reduce the R&D costs of our customers. Should an SME company need equipment which we do not have, we can always look around in our network. And if we can also serve other customers with specific facilities, I can imagine that we invest in them together.’ For that matter, Senbis works with a number of parties, such as universities, in various research projects.

The company is now very busy working out a number of promising projects in more detail. This includes the development of a compostable horticultural twine and an alternative for dolly rope which hangs beneath fishing nets.

Growers of crops such as tomatoes, capsicums and cucumbers currently mainly use twine which is based on fossil raw materials to guide their products to grow upwards in the greenhouses. ‘At the end of the season they need to get rid of the plants. But that is a difficult job because the twine has become entangled in them,’ explains Nijhoving. ‘This means that growers have a large waste stream for which they incur large costs to dispose of it. Moreover, it is not a sustainable solution.’

Starting production

Senbis Polymer Innovations developed a compostable twine based on polymer lactic acid, which has since undergone various field tests. ‘It is a technically challenging project because the mechanical properties have to ensure that the plants in the greenhouses do not fall down,’ says Nijhoving, who has high expectations of the new product. ‘Our twine is now hanging in greenhouses in different countries to test how it works.’ If these tests go off successfully, we will start production at the end of the year.’

The company is also participating in a pilot project of VisPluisVrij to find an alternative to the fossil raw material-based dolly ropes. Dolly ropes are hung in clumps under the fishing nets of fishing boats, mainly beam trawlers. These nets drag over the sea floor. To prevent the nets from wearing out too fast, the fishermen use dolly ropes. During the fishing, the plastic wires come loose and end up in the sea. Dolly ropes are made from polypropylene and are therefore not biodegradable. As a result, birds become caught in them, plastic particles end up in the food chain and the beaches are polluted. ‘We are working with VisPluisVrij to develop a biodegradable alternative, to reduce the plastic soup in the oceans.’