Bioplastics are not created equal. Roughly speaking there are two types: the so-called drop-ins that replace fossil plastics 1 on 1, such as bioPE, bioPET and bioPP, and new bioplastics, such as polylactic acid (PLA) and the more recent polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA). Their chemical composition differs and they have different properties. Both types can be used to produce a wide range of products. Ranging from hard caps, bottles, pipes, toys and chip trays to flexible garbage bags, coating, sandwich bags, films and foils for food packaging.

The thing that bioplastics have in common is that the raw material is agricultural and therefor renewable. The share of such plastics of the total volume of plastics is still limited to approximately 1%. This is rapidly changing, because demand is exploding. This makes the need for answering a number of outstanding questions all the more urgent.

Alternative to fossil

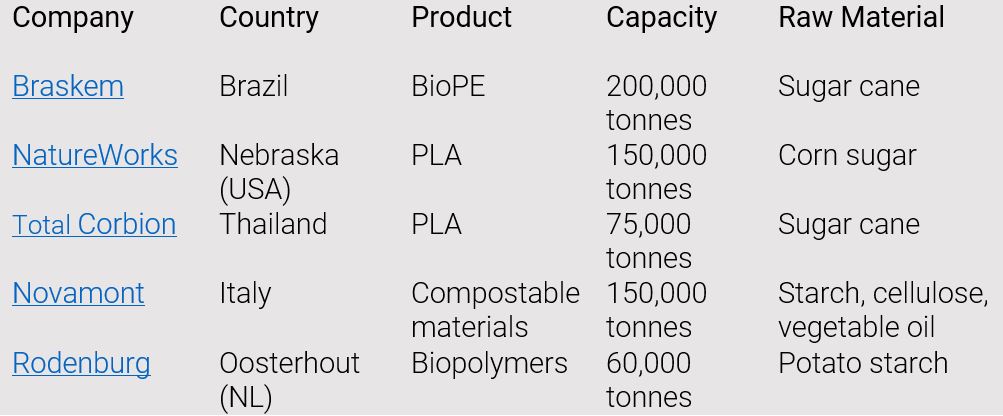

But what problems do bioplastics actually solve? “The primary advantage of bioplastics is that they are an alternative to fossil raw materials,” says Erwin Vink of the sector association Holland Bioplastics. “Everyone is convinced that we need to get away from these raw materials.” Marco Jansen of the Brazilian company Braskem that produces bioPE from sugar cane, endorses this: “We offer a solution to finite raw materials. Furthermore, our CO2 emission is negative. We save 5 tonnes of CO2 for every tonne of PE that is replaced by bioPE.”

The advantage of the new bioplastics is that sometimes they have better properties. For example, take PLA for refrigerators as a replacement for polystyrene. Vink: “This has two advantages. Less CO2 is released during production and PLA insulates better than polystyrene. However, these refrigerators are not yet on the market.” Furthermore, PLA and PHA are compostable in industrial plants.

Food

Because bioplastics are derived from crops, this immediately provokes the debate about whether they compete with food production. Jansen and Vink are adamant on this point: the answer is no. “In Brazil there are many abandoned grass areas,” says Jansen. “Government has designated these areas for sugar cane as a basis for food and bio-ethanol. Sugar cane thrives on poor soil. We are currently using 0.02% of what is available. We definitely do not want to compete with food production. Vink, who is associated with the PLA producer NatureWorks, also challenges this criticism. “We are currently using corn sugar. The quantity we are using corresponds to 0.06% of production in the US. Peanuts compared to the 30-40% of food wasted every year.”

In addition, there are initiatives for producing PLA from residual vegetable flows. “The applications already exist,” says Vink, “but primarily for biofuels. It is still too expensive to convert these into high-quality bioplastics. The processes are technologically difficult. When you have to extract sugar from a plant, you must first pull the plant apart using brute force. Nature has expressly created robust building blocks. I estimate that in ten years’ time the technology will nevertheless have advanced to such an extent that it is economically attractive to exploit agricultural residual flows.”

Growing demand

The demand for bioplastics is unmistakably increasing. “We notice that people are looking for sustainable alternatives,” says Jansen. “Last year there was a significant increase in demand from Europe and Japan. This primarily concerns products for which recycled products do not qualify, such as food packaging, cosmetics and toys, or products with specific properties, such as transparency.” At the present time Braskem is barely able to meet demand. “We expect that starting next year, demand will exceed supply. This is why we are planning to expand existing capacity. This will take at least three to four years.”

We save 5 tonnes of CO2 for every tonne of PE that is replaced by bioPE

According to Vink, the demand for PLA is many times greater than the available supply. “We need more capacity. PLA producers are currently assessing whether there is room for a third or fourth plant. For example, NatureWorks is investigating various options for building a plant outside the USA. The Netherlands could be an option, although a lot still needs to happen to properly organise the processing of bio and other plastic waste.”

A new plant requires significant investments. According to Jansen the current plant cost in the order of € 300 million. “That expansion will certainly happen. We were the only bioPE producer for the longest time. Competition is now starting to emerge. We welcome that. This benefits the market. Today, buyers are wary because they do not want to be dependent on a single producer.” “The same applies to PLA,” Vink adds. “We too welcome Total Corbion’s initiative of building a PLA plant in Thailand.”

High costs

Production costs are an issue. “Just considering the material alone, PLA is more expensive than fossil plastic,” says Vink. “And you still have to convert it into a product. The drawback is scale. At a minimum you would need a 600,000 tonne plant to be able to compete with PP and PE.” The same applies to bioPE. Jansen: “We convert bio-ethanol into bioPE. The technology has not yet advanced to the stage where this can be done efficiently. For the production of one tonne of bioPE you require twice as much bioethanol. In other words, the yield is less than 50%. The other half is a cost item.”

These higher costs are passed on to buyers: the packaging industry, brand owners, retailers and ultimately the consumer. “They are prepared to pay a higher price provided it is no too much,” Vink suggests. “But we are on the right side. It is up to bioplastic producers to scale up.” Jansen shares his optimism. “Costs for brand owners and retailers can certainly be higher, provided that they can market the product differently, for example by garnering greater appreciation. People want sustainable products. I perceive more opportunities than challenges.”

We are on the right side. It is up to bioplastic producers to scale up

Recycling versus composting

The heated debate about bioplastics is all about the waste phase. Everyone is convinced that bioplastics are not the answer to the plastic soup. Where the viewpoints diverge is in relation to the issue of recycling versus composting. Government and waste processing companies give priority to recyclability. Holland Bioplastic supports this position, but also believes there should be a place for compostability. “Recyclability and compostability are at odds with each other,” in the opinion of Tim Brethouwer, Advisor to the Association of Waste Processing Companies. “The easier it decomposes the weaker the products that can subsequently be made from it. Compostable bioplastics do not belong in the plastics recycling bin and recyclable bioplastics do not belong in the kitchen waste container. We need to avoid this contamination crossover.”

The discussion shifts to PLA. PLA can easily be separated and recycled. In addition, the thinner PLAs are biodegradable in an industrial composting plant; however they do not decompose in water or in soil. Drop-ins are not compostable. “You can recycle bioPE together with the regular plastics because they are chemically identical,” Jansen explains. This is why waste processing companies do not object to these products.

Confusion

Precisely because PLA is compostable as well as recyclable, this is creating confusion among consumers. Nobody wants this. Vink: “It is complicated and as a result there is a great deal of misinformation. People do not understand it and therefore do not purchase it. This is an obstacle. You have to constantly tell people what bioplastics are and what you can and cannot do with them.” Brethouwer: “You have to make it easy for consumers. Right now they do not understand it. 4-5% of kitchen waste is contaminated and as a result we have our hands full with this. What we are not saying is that compostable bioplastics reduces this contamination. On the contrary. Increased confusion leads to increased contamination.”

Waste processing companies therefore want the focus to as much as possible be on the recyclability of biobased plastics and explicitly not on their compostability. “It is better to put PLA on the market as a renewable and recyclable material,” Brethouwer emphasises. “When a new type of plastic enters the market in large volumes, waste processing companies can modify their plants accordingly. This requires investment and therefore the benefits must be significant. You must involve the entire lifecycle in this. In addition, coordination is required to prevent all kinds of new types of plastic from entering the market in small volumes.” Vink adds: “We support maximum recyclability, but if it is incinerated you’ll produce green electricity. Perfect as a temporary solution isn’t it?”

Difference in interpretation

At the same time there is a lot to be said for composting. Producers and waste processing companies agree that you should only compost if it is worthwhile to do so. But the interpretation of what is worthwhile may differ. Brethouwer: “We are inundated by useless compostable products. I quickly counted 200 products. Ice trays, cutlery, pens, shoes. We need to get rid of these things. They do not add anything. How did we let things get this far astray?” Vink also acknowledges this. “As a sector we produced biobased pens as a gadget at one point in time. The pen includes a metal spring, a chromium ring and ink. That is not a good design. The compostable shampoo bottles that appeared for a period of time are not a good solution either. Shampoo residues always stay behind in these bottles and microorganisms are not able to withstand these residues.”

We are inundated by useless compostable products. They do not add anything. How did we let things get this far astray?

Useful composting

But what is worthwhile in that case? Compostability in any case must provide added value. For example, by significantly contributing to more and cleaner kitchen waste. Fruit stickers are the best known example. They now end up in the kitchen waste container. Vink: “These PE stickers end up on land and in oceans as microplastics. Furthermore, they gum up the installations. If you make them biodegradable, you solve this problem.”

Next take the teabags and coffee pads. Composters would like to have the tea leaves and the coffee drabs, but not the PE packaging. Yet, people throw these products into the kitchen waste containers en masse. According to the existing list of the National Waste Management Plan this is not permitted. “But no one is familiar with the contents of this list,” Brethouwer sighs. “Producers must align themselves with daily practice. But in that case all teabags must be compostable. It is all or nothing. It is distressing that corporations such as JDE and Unilever make them from plastic. Make them compostable. They absolutely are totally responsible for this.” Vink does not agree with this: “Companies have already gone far beyond this. In the UK, Unilever brands such as PG Tips and Clipper are already bringing compostable teabags on the market. Every teabag that you convert is a gain and lowers the leakage of microplastics into the environment. JDE too has already developed PLA coffee pads that are compostable. The all or nothing principle only holds back market development.”

Useless

In addition there is a grey area, such as kitchen waste bags, herb trays and coffee capsules. According to Vink these are also worthwhile applications. “There are still more, but let’s start with those, so that the entire system can get used to them.” Brethouwer: “Compostable kitchen waste bags: excellent, by all means. But no compostable bags in the vegetable department of the supermarket. You should not throw any empty containers in with the kitchen waste. Why would you do this? It would entice people to throw kitchen waste into the green bin. However, research shows that few consumers collect their cutting waste in the packaging.”

Facts

Wageningen University & Research (WUR) is putting the final touches on its research into the compostability of bioplastics. This could serve as a basis for a list of worthwhile compostable bioplastics. Vink: “This makes it possible to engage in a debate based on facts rather than opinions. This should result in a Governmental Decree: here’s what we are going to do. In my opinion government should be able to clamp down. Compostable fruit stickers are mandatory in Belgium. In the Netherlands it is difficult to make something mandatory.” Brethouwer shares this opinion. “I wish the Dutch government would mandate this as well. Government is not about to introduce regulations that would make teabags and coffee pads compostable. As far as we are concerned, we should come up with a list of worthwhile compostable products together with government. Government should then also ensure that other compostable products no longer are permitted to carry the seedling logo. This is confusing.”

A great deal of work still remains to be done

Who should make the next move? Producers must create clarity at the beginning and government at the end. “The will to do so is there on all sides,” says Jansen. “Never before have I seen such rapid change. Brand owners should include this option as a requirement in their product design. Retailers can exercise a great deal of influence with their own brands. And in fact this is happening.” Vink: “A great deal of work still remains to be done. Things are moving slower than I thought ten years ago. Moving forward together is a challenge. But things should not be such that there is nothing on retailer shelves. That would cause consumers to become disappointed and bring things to a halt.”