The first day of the event was reserved for companies in the bio-based economy looking for cooperation partners during the finals of the Tech Tour Bio-based Industries 2023 programme. On the second day, the Circular Valley Forum discussed solutions to current societal challenges around the circular economy.

Prime Minister Hendrik Wüst of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and his Flemish colleague Jan Jambon kicked off the Forum with a historic moment: they signed the first agreement of cooperation between two regions from Germany and Belgium on the circular economy.

“We do not want to realise the circular economy alone,” Hendrik Wüst emphasised. “No country can do that alone, because in the circular economy it comes down to mass and the involvement of many different players. Flanders, as a strong industrial location in the Benelux, is a very valuable partner for us.”

The regions have been working together for years on hydrogen, the chemical industry and the digital economy, and the circular economy is a natural progression. Over the next five years, NRW and Flanders intend to exchange knowledge, launch pilot projects, train specialists and apply for joint funding, as well as establish a brand for promoting the circular economy. Wüst: “Setting common goals on climate and economy will benefit both sides. By doing so, we also reduce our dependence on fossil fuels and enter a future common market. By linking climate goals with economic prosperity, welfare and social security, we can secure democratic stability.”

“Let us turn our vision into concrete measures”

Jan Jambon (Flemish Government)

This will also impose commitments on politicians: “We have to find a way in this: new thinking, new regulation, creating new legal frameworks for the several markets. Moreover, we can only realise the great opportunity presented by the circular economy by thinking big and cooperating internationally. The more countries, the more parties join this initiative, the better. We are now leading the way. We are doing so with the intention of being an example within Europe and showing that it works.”

Catalysts

North Rhine-Westphalia and Flanders can become the recycling centre of Europe, according to Jan Jambon, Minister-President of Flanders. “I firmly believe in the connection of Circular Flanders and Circular Valley as catalysts for cross-border cooperation in the circular economy. And we are open to other partners wanting to join us. Thus, the Netherlands is an obvious partner for the next phase, as our regions are complementary. Together, we are the industrial and innovation heart of European industry. Together, we are stronger. Each with its own specialism, but each with the same goal: to close material cycles as much as possible through the use of technology and innovation.”

According to Jambon, the circular economy will also be one of the main themes during the Belgian presidency of the European Council in 2024. “We hope that together with all European member states we can formulate starting points to set priorities around the circular economy in the future work programme of the next European Commission. Let us turn our vision into concrete measures and contribute to a sustainable future for our regions.”

Acceleration necessary

For Harald Schwager, Deputy Chief Executive Officer of Evonik, borders do not actually exist. The chemical company has sites in various locations in NRW, as well as in Antwerp and Amsterdam. “The challenges we face today do not stop at national borders. Cross-border cooperation is therefore indispensable to shape a sustainable future,” he said in his keynote speech.

Schwager is convinced of the need to accelerate the transition to a circular economy, in which the chemical industry has an important role to play. “We are now feeling the mistakes we have made over the past 100 years with full force. Some just see that as an opportunity and act accordingly. Unfortunately, it also means that many companies that once made us great are now investing outside Europe. And we continue to move at a snail’s pace. Failing innovation, failing access to clean energy and poor political regulatory frameworks are putting us at a disadvantage.”

In a circular economy, new business models emerge and partnerships gain importance. Today’s everyday products disappear and new ones emerge. But one thing does not change, according to Schwager, and that is the key role of the chemical industry. “We are traditionally solution providers, drivers of innovation for many industries. Without chemistry there is no sustainable economy, no energy transition and no green transformation.”

Decarbonisation

At the same time, industries face the challenge of decarbonisation: exchanging fossil raw materials for more raw materials from recyclates, biomass and waste. Of the 400 million tonnes of plastics produced worldwide last year, about 10% are now made from recycled or biobased feedstock. In Europe, the proportion is even twice as high: one-fifth. Can the European industry maintain this lead in the longer term? Schwager: “I doubt it. The market share of European plastics producers has halved in the past year. Many other industries are seeing a similar decline. We do have the right mindset for this new industrial revolution to succeed. Entrepreneurs are ready to invest, but without smart regulations and affordable energy, we will not succeed. First of all, we are missing a legal framework that gives investors legal certainty. This needs to be regulated at the European level.”

Clean and, above all, affordable energy for energy-intensive companies such as the chemical industry is also indispensable. “To give an example: Evonik pays 14 cents per kilowatt-hour of electricity, plus taxes, on the European power exchange. In the US, the rate is just 2 cents. Such differences make it difficult for the European industry to compete internationally.”

Schwager does not see state aid as a solution to this competitive disadvantage. “What we need above all is a clear signal from politicians that industry which creates value, including energy-intensive industry, is still needed in Germany and in Europe.”

“Chemical industries are the drivers of sustainable transformation”

Harald Schwager (Evonik)

Some economists argue that a radical transformation is necessary and that Europe might be able to continue without any energy-intensive industry. According to Schwager, this is impossible. “We are the drivers of sustainable transformation. We contribute to the well-being and preservation of high-quality jobs and thus to unity, a sense of purpose and the survival of the welfare state. In Germany alone, we pay €50 billion a year in taxes and every second pension euro in our country comes from the chemical industry. We are creating a better future. We are building the industry of tomorrow with respect for the creation and without destroying the old one. That, in every sense, is circularity.”

Biobased products

In several panel sessions following, further discussion took place on energy transition as a necessity for the circular economy, the role and responsibility of business in making circular products available, and cooperation in the value chain for biobased products that provide an alternative to products from fossil raw materials.

“We gain nothing if high-quality biobased products only last a single linear life cycle”

Thomas Rodemann (Vorwerk Elektrowerke)

Bio-based raw materials are especially important for post-consumer products that are difficult to recycle. But that does not mean they should not be recyclable themselves. “We have gained nothing if we make high-quality biobased products that then only last a single linear life cycle,” said Thomas Rodemann, board member of Vorwerk Elektrowerke. Circular design is equally important here: products should be made of mono-materials as much as possible and designed in a modular way so that they can be easily disassembled, sorted and mechanically recycled. Producers should also take products back in order to reuse the optimised materials and thus extend their life span. This is crucial from an overall cost perspective. However, current pricing mechanisms are rooted in linear thinking. They focus on minimising initial production costs, which does not optimise products for reuse or recyclability. “If we keep thinking this way, the circular economy will never get off the ground,” he says.

Collection

How to get products back to the manufacturer at the end of the life cycle is still a challenge. Markus Helftewes, Managing Director of Der Grüne Punkt, an organisation set up to collect plastics, also sees this. “In the EU, only 26% of collected plastics are recycled; 36% are incinerated and 38% end up in landfills. This is a shame, because many optimised plastics are lost as a result.”

“A barrier remains as long as burning or dumping plastics is cheaper than recycling them”

Markus Helftewes (Der Grüne Punkt)

“We need to move towards a higher recycling percentage: first mechanically and if that is no longer feasible: chemical recycling. It will require regulation, but we also need companies dedicated to achieve this. They need to be supported and encouraged, so that they gain ‘fans’, for example, who invest and donate ideas. Unfortunately, there will still be a barrier as long as burning or dumping plastics is cheaper than recycling them.”

Agriculture

Both mechanical and chemical recycling are partial solutions to the still growing global demand for renewable resources. There is also a growing need for new, more sustainable materials and chemicals. CO2 is a potential feedstock for this, but a major part will have to come from agricultural crops. As a result, the debate about using agricultural land for fuels or chemicals, rather than food, is flaring up again.

“New digital and biological solutions can help make agriculture regenerative”

Frank Terhorst (Bayer Crop Science)

As Frank Terhorst (board member of Bayer Crop Science AG) puts it, there is enough arable land worldwide to do both – 1.4 billion hectares. Of these, less than 8% are currently used to grow crops for biofuels and less than 1% for biobased plastics. “Moreover, we now have the opportunity to make agriculture regenerative through new digital and biological solutions. With intermediate crops on farmland, or crops on degenerate soils unsuitable for growing food, we can grow energy crops that do not compete with food production. Think of all kinds of weeds that can be harvested for biodiesel production. All of this significantly reduces the overall CO2 pressure.”

Down the drain

Biobased or not, if substances end up in the environment, they must be built to break down in those conditions. This applies, for example, to personal care products and laundry detergents that are washed away and end up in the sewer. They cannot be collected for recycling. Henkel, which produces these products, takes this into account in its product strategy, says Frank Meyer (Senior Vice President of Henkel Consumer Brands): “We focus on complete biodegradability of these substances. Moreover, we use renewable raw materials for 50% of our plastic packaging and want to move towards 100% step by step. Together with BASF, we have further developed a way to replace fossil fuels in our production processes with biogas from residual products.”

Most circular solutions requiring substantial investments are, for the time being, more expensive than continuing with the linear economy and fossil fuels. However, the prevailing view in business is that proceeding on the current path is not an option. It is seen as a moral obligation to invest in sustainability. Customers, NGOs and end-customers also demand it. Moreover, governments at national but also European level are providing several incentives, think of various funds linked to innovation, regional development and the EU Green Deal.

Rest of the world

The US, China and India are also currently working hard to realise circular and biobased production. The US, for instance, are pumping in a billion dollars with the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). Moreover, energy is cheap there, so production costs are much lower. Money is not the only thing that matters, however, argued Lauren Kjeldsen, member of the Executive Board of Evonik, during a workshop on international incentives. In Europe, entrepreneurs face overregulation and slow bureaucratic procedures. In stark contrast is the responsiveness of decision-makers in the US: “The certainty that in the US everything is resolved on time, is an incentive itself to establish a presence there. The same applies to a small state like Singapore. You feel there that they recognise that strong industrial companies are both needed and welcome.”

“Transparency and clarity are much more important to entrepreneurs than financial incentives”

Surendra Patawari (Gemini Corporation)

Elsewhere in the world, the red carpet is also being rolled out for industrial enterprises. Surendra Patawari, CEO of Gemini Corporation: “The Indian Ministry of Energy has a budget of 40 billion to distribute. The director of loans Jigar Shah will simply say: ‘If you do this, you will get that.’ An approach like this provides clarity.” In Europe, the attitude leans more towards distrust of the industry. “Here, you are told: ‘If you don’t do this, you will not get that.’ It is a completely different approach. Transparency and clarity are missing. They are ultimately much more important to entrepreneurs than financial incentives.”

This was also emphasised by Mona Neubaur, Minister for the Economy in NRW and Patron of the Circular Valley Forum. “We must not only declare our ambitions, we must dare to take concrete measures that can be realised unambiguously and without fuss by the business community, shoulder to shoulder with the scientists and the responsible ministries. For time is running out. If we look at the pace at which we are reducing CO2 emissions, it will take to 2065 to get to the point where we should be in 2040.”

She referred to the 1980s, when acid rains threatened Europe’s forests. The Federal Government then took the drastic measure of mandating the use of desulphurisation facilities for the chemical industry. It not only saved the forests, but also gave birth to a whole new industry in Germany at the forefront of desulphurisation technology. “I wish we could see the business models behind it. Indeed, in the same way, the circular economy will be a growth engine for our economy and industry.”

Gamechangers

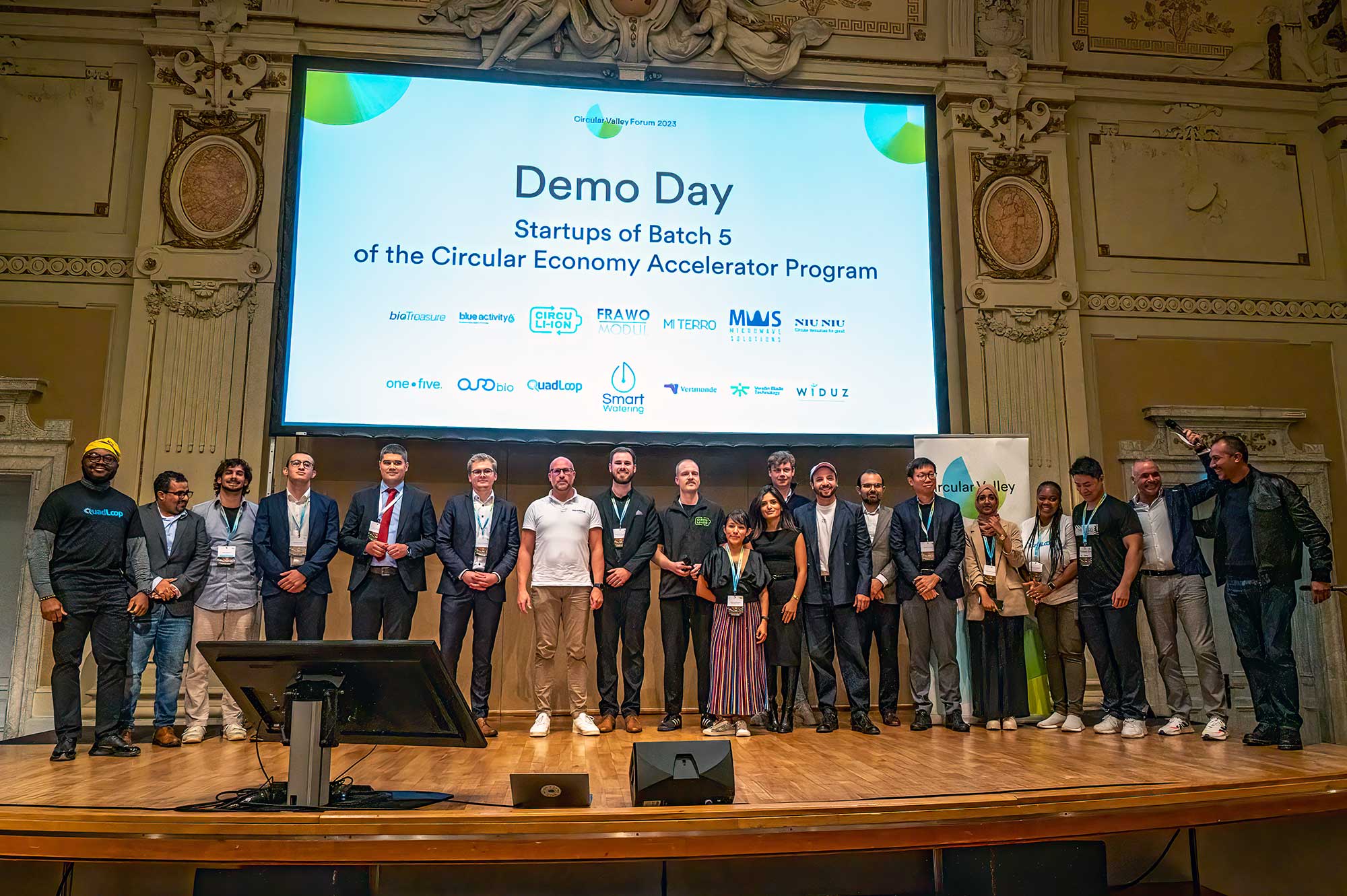

The Forum concluded with the ‘Demoday‘: pitches from 14 young startups that were mentored by the Circular Valley Community from September this year. They focus on diverse facets of circularity: alternative raw materials, building materials, packaging, water and recycling. Remarkably, these startups came from all over the world: Germany (4x), the US (2x), Luxembourg, Switzerland, Serbia, Ecuador, Nigeria, Singapore, Yemen and Mexico.

The next ‘Tech Tour Circular event’ will be held on 23 and 24 April 2023, in Ghent, Belgium. Among other things, it will focus on the bioeconomy, chemicals and materials.

This article was produced in cooperation with the Bio-based Industries Consortium