To explore how far this transition has progressed — and where its limits currently lie — the Bio-based Industries Consortium (BIC) recently hosted a webinar on fibre-based packaging. The aim, as BIC Executive Director Dirk Carrez outlined in his opening remarks, was not to promote a single material or technology as a universal solution, but to examine where bio-based options already deliver tangible value and where further innovation is still required. The bioeconomy, he argued, is about making the right material choices for the right applications, supported by close cooperation between industry, innovators and policymakers.

That perspective framed a discussion bringing together three complementary viewpoints: a market-wide outlook from Smithers, the practical realities of material innovation from PaperFoam, and a system-level approach to flexible packaging from Paptic.

Growth engine with limits

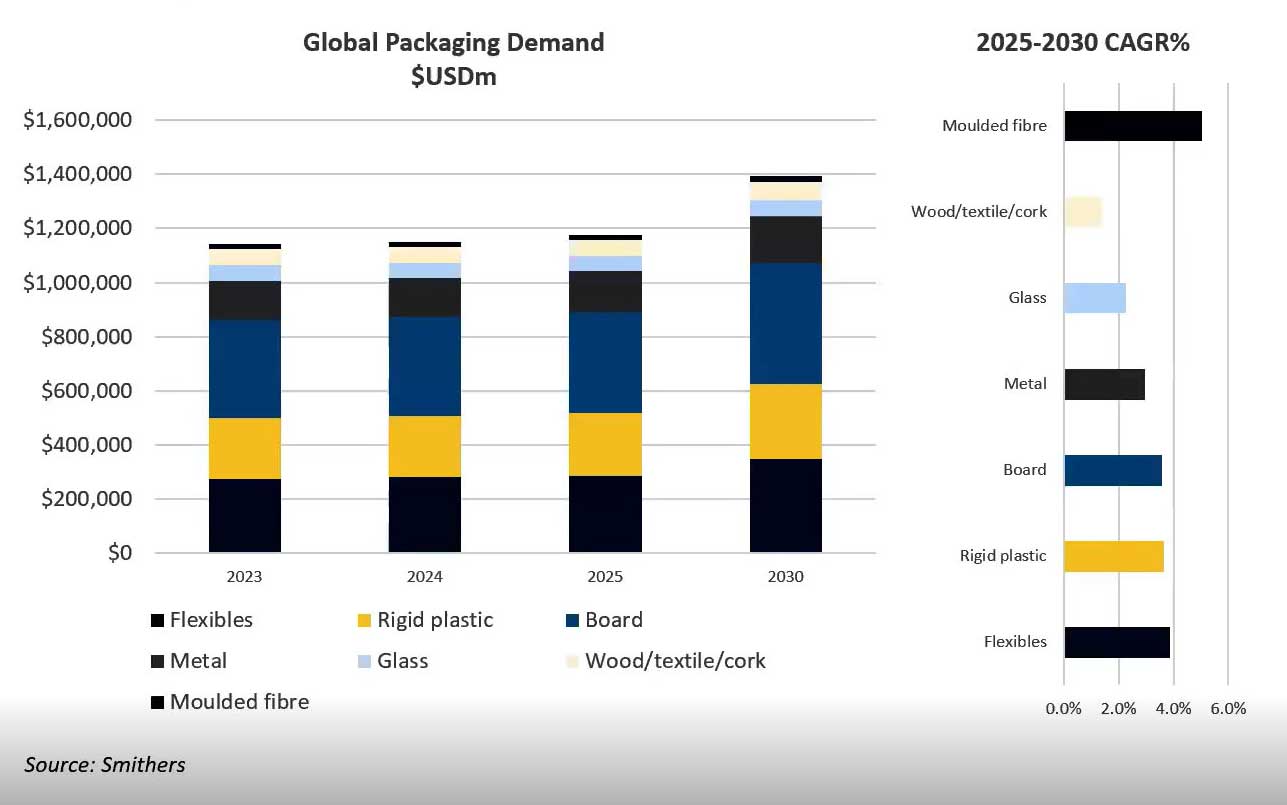

From a market perspective, Ciaran Little, Vice President Global Consulting at Smithers, left little doubt about the strategic importance of packaging for the paper industry. “Packaging is really the growth engine for the paper industry,” he said. The global packaging market is now valued at around USD 1.174 trillion across all material types and continues to expand at roughly 3.5 per cent per year, with fibre-based formats taking an ever-larger share.

That growth, however, is uneven. Fibre-based packaging is not a single market but a collection of distinct segments, including corrugated board, folding cartons, liquid paperboard, flexible paper packaging, moulded fibre and labels. Each follows its own trajectory and faces different technical constraints. In absolute terms, corrugated board remains dominant and is forecast to grow by 22 million tonnes by 2030, driven by e-commerce and logistics.

The most dynamic growth, however, is occurring elsewhere. Moulded fibre is expected to grow at around 5% CAGR, while flexible paper packaging is forecast at approximately 3% CAGR. “Moulded fibre will be the highest growing packaging format overall,” Little noted — a reflection of how fibre-based solutions are gaining ground in applications traditionally dominated by plastics.

Even so, Little was keen to temper expectations. Fibre-based packaging does not herald the demise of plastic. “There are numerous challenges to replacing plastic in terms of functional performance, commercial attractiveness and overall value proposition,” he cautioned. In many applications, barrier performance, puncture resistance are critical to maintaining food safety and minimising food waste. Plastics also often retain cost and processing advantages. At the same time, the plastics industry itself is evolving, particularly through more recyclable mono-material designs.

Europe occupies a pivotal, if complex, position in this transition. “Consumers in Europe tend to be the most eco-conscious… and it’s also the most intense regulatory environment,” Little observed. Frameworks such as PPWR, EPR and SUPD are accelerating the shift towards circularity, but they also introduce uncertainty while definitions, test protocols and enforcement mechanisms are still being refined. From a technology standpoint, Little sees particular promise in dry-forming processes for moulded fibre and in next-generation barrier coatings for flexible paper packaging. One condition, he stressed, is essential: “For consumers to continue to have trust in recycling, brands will have to make sure that inks, coatings and adhesives are recyclable at scale.”

Sustainability meets regulatory reality

Mark Geerts illustrates how these dynamics play out in practice. The Netherlands-based company PaperFoam has been producing bio-based foam packaging since the late 1990s, using potato starch and cellulose fibres in a proprietary baking process. “The mould is kept at 200 degrees Celsius,” Geerts explained, allowing water to evaporate and leaving behind a lightweight, dimensionally stable foam.

The environmental credentials are compelling. “It’s only 1.2 kilograms of CO₂ per kilogram of product,” Geerts said. Thanks to its low density, the carbon footprint per packaging item can be 60 per cent lower than that of EPS or conventional moulded fibre. Today, PaperFoam supplies packaging for electronics, cosmetics, food and medical applications at industrial scale across multiple regions.

Geerts described a marked shift in market sentiment. Where the company once struggled to gain access to decision-makers, it is now increasingly approached proactively — sometimes at board level. Protection remains the primary requirement, but design quality and sustainability now play a far greater role. The smooth surface and colour flexibility of PaperFoam enhance the unboxing experience, while its high bio-based content aligns neatly with corporate ESG strategies.

Paradoxically, it is precisely on sustainability that PaperFoam encounters regulatory barriers. Technically, the material is both compostable and recyclable within the paper stream, yet it fails to meet the formal definition of ‘recyclable at scale.’ “According to the official test methods, 100 per cent PaperFoam is too sticky,” says Geerts, referring to the CEPI/4EverGreen test. “But in real-world mixed waste streams, it would pass the test.” In practice, PaperFoam will always represent a small fraction of a mixed paper stream.

With regulation setting the rules of the game, Geerts has opted to adapt rather than resist. The company is developing PaperFoam 4.0, a fibre-richer formulation capable of passing the 100-per-cent test. This involves trade-offs — slightly higher weight and a shift in emphasis away from maximum climate optimisation — but ensures regulatory compliance. In parallel, PaperFoam is investing in extrusion-based technologies using starch and fibres to develop thicker foam, allowing it to serve as a genuine alternative to EPS in heavier-duty applications. For Geerts, this underlines a broader truth: innovation often has to bend to existing systems, even when those systems lag behind technical reality.

Making change compatible

If PaperFoam addresses formed packaging, Paptic focuses on one of the most demanding segments of all: flexible packaging. According to Heidi Saxell, Chief Product Innovation Officer, success here depends less on radical material change than on seamless integration into existing industrial systems. “They are basically drop-in materials for flexible packaging lines,” she said.

Founded in 2015 as a spin-off from Finland’s VTT Technical Research Centre, Paptic moved rapidly to industrial production, launching commercial manufacturing in 2018 through partnerships with existing paper mills. Its fully fibre-based material offers properties conventional paper lacks — flexibility, tear resistance, and foldability — while remaining compatible with paper recycling systems.

Production speed is critical. “We have demonstrated over 1,200 pieces per minute, which is the same speed as plastic packaging,” Saxell explained. This makes Paptic viable for high-volume markets such as hygiene packaging, e-commerce mailers, and reusable carrier bags. Single-wrap feminine hygiene products, in particular, represent a promising growth area due to their stringent performance and aesthetic requirements.

Notably, Paptic has chosen not to pursue compostability. “We have decided actively not to go yet to compostability… PPWR and recyclability at scale is the licence to play,” Saxell said. By aligning fully with existing recycling infrastructure, the company aims to reduce friction across the value chain and accelerate adoption. Saxell also highlighted the inherent risk of innovation in packaging. “There is no easy trick. It is hard work,” she said, adding that progress depends on collaboration — and, at times, on competitors working together.

Progress through alignment

Taken together, the three perspectives reveal fibre-based packaging as a sector advancing at pace but constrained by real-world trade-offs. Smithers outlines the scale of market growth and the functional limits of paper relative to plastic. PaperFoam demonstrates how advanced material innovation can clash with regulatory definitions. Paptic shows how compatibility with existing systems can determine commercial success.

The message is clear: the future of fibre-based packaging does not lie in a single, universal solution, but in targeted choices for specific applications. Or, as Little put it, “Fibre-based packaging is a real hotbed of innovation.” Unlocking its full potential will depend on aligning material development, regulatory frameworks, and industrial reality — a challenge that sits at the heart of the bioeconomy’s next phase.

This article was written in collaboration with the Bio-based Industries Consortium (BIC)

Top image: T-Mobile packaging by PaperFoam